The Valley of Pharaohs: Journey into Egypt’s Eternal Afterlife

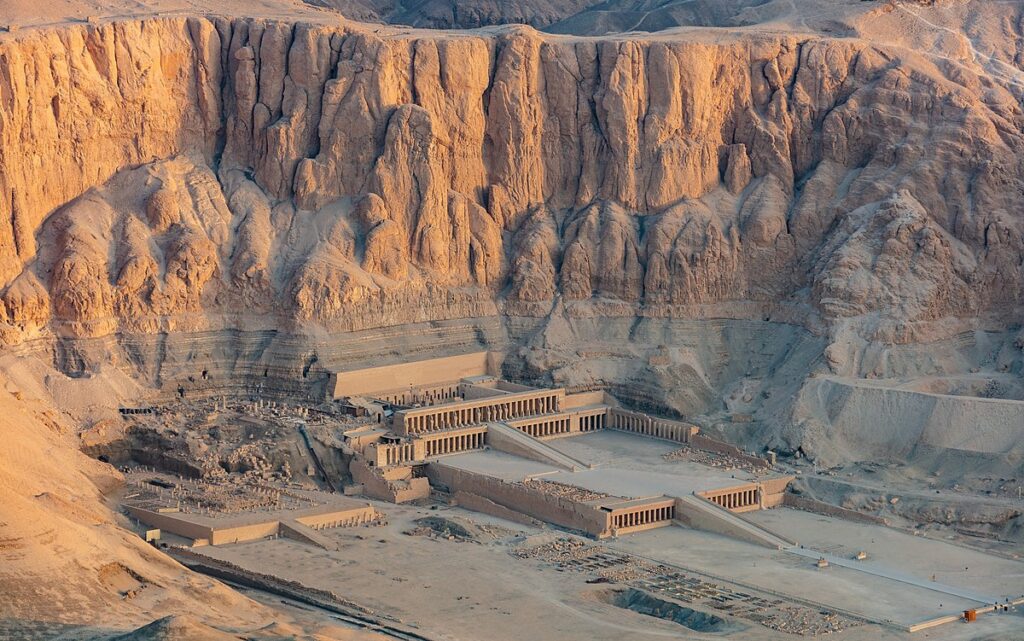

The rulers of the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties of Egypt’s prosperous New Kingdom (c.1550–1069 BC) were buried in a desolate dry river valley across the river from the ancient city of Thebes (modern Luxor), hence its modern name of the Valley of the Kings. This moniker is not entirely accurate, however, since some members of the royal family aside from the king were buried here as well, as were a few non-royal, albeit very high-ranking, individuals. The The Valley of Pharaohs is divided into the East and West Valleys. The eastern is by far the more iconic of the two, as the western valley contains only a handful of tombs. In all, the Valley of the Kings includes over sixty tombs and an additional twenty unfinished ones that are little more than pits.

The site for this royal burial ground was selected carefully. Its location on specifically the west side of the Nile is significant as well. Because the sun god set (died) in the western horizon in order to be reborn, rejuvenated, in the eastern horizon, the west thus came to have funerary associations. Ancient Egyptian cemeteries were generally situated on the west bank of the Nile for this reason.

The powerful kings of the New Kingdom were laid to rest under the shadow of a pyramid-shaped peak rising out of the cliffs surrounding the valley. The selection of even the specific valley in which the royal tombs were excavated was not left to chance. The pyramid was a symbol of rebirth and thus eternal life, and the presence of a natural pyramid was seen as a sign of the divine. This entire area, and the peak itself, was sacred to a funerary aspect of the goddess Hathor: the “Mistress of the West”.

The isolated nature of this valley was yet another reason for its selection as the final resting place of the pharaoh. Tomb robberies occurred even in ancient times. The Egyptians were aware of this, having seen the a fate of the Old and Middle Kingdom pyramids, so they opted for hidden, underground tombs in a secluded desert valley. The first New Kingdom ruler that is confirmed to have been buried in the The Valley of Pharaohs was Thutmose I (c.1504–1492 BC), the third king of the Eighteenth Dynasty. According to Ineni, the high official who was in charge of the digging of his tomb: “I oversaw the excavation of the cliff-tomb of his Person [the king] in privacy; none seeing, none hearing.”

Summary of the RPG “The Valley of Pharaohs”

Publisher: Palladium Books (a company known for Rifts and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles & Other Strangeness).

Publication Date: 1983.

Setting: New Kingdom Egypt, 1450 BCE (18th Dynasty)—a very specific and rich historical period.

Core Concept: Players take on roles within Egyptian society (Noble, Clergy, Bureaucrat, Commoner) with specific occupations (Soldier, Priest, Scholar, Merchant, Thief).

Critical Reception & The Game’s Flaw

As the reviews from Jonathan Tweet and Rick Swan indicate, the game was critically panned, despite its promising premise. The main criticisms were:

Lack of Adventure Hooks: The biggest failure was that it didn’t answer the question, “What do the player characters do?” Ancient Egypt was a highly structured, bureaucratic, and orderly society. The game rightly pointed out that the typical D&D model of “armed adventurers” didn’t fit, but it failed to provide a compelling alternative. How does a Scholar, a Bureaucrat, or a Priest have an “adventure”?

Shallow Rules: The game systems, especially for magic, were underdeveloped. The magic system was generic and didn’t feel integrated into the Egyptian worldview or religion.

Missed Potential: Despite having 20 pages of historical background, the game didn’t successfully translate that research into gameplay mechanics or compelling narrative structures. It provided the setting but not the story.

What Could a “Valley of Pharaohs” Adventure Be?

A modern game designer might learn from these criticisms and create adventures that are authentic to the setting. Adventures wouldn’t be about dungeon crawling, but about:

Political Intrigue: Securing favor at the Pharaoh’s court, uncovering a plot against the vizier, or negotiating with a troublesome provincial governor.

Religious Mysteries: Investigating an alleged desecration of a temple, escorting a sacred relic up the Nile, or interpreting ominous dreams for the royal family.

Bureaucratic Quests: Being sent by a high official to audit the grain supplies in a distant nome (province), only to uncover corruption.

Tomb Protection: Acting as Medjay (police/guards) to investigate and stop a ring of tomb robbers targeting the necropolis.

Conclusion

So, while the geographical location “Valley of the Kings” is the correct term, “The Valley of Pharaohs” is indeed the title of this specific, niche RPG. It serves as an interesting case study in game design—a game that was praised for its historical research but ultimately failed because it didn’t provide a framework for turning that history into a fun and engaging role-playing experience.

It’s a great example of how a fantastic setting alone is not enough; the rules and adventure design must support players in living out a fantasy within that world.

The Most Famous Tombs of the Valley of the Pharaohs

KV62 – Tomb of Tutankhamun: Howard Carter’s discovery and treasures.

KV17 – Tomb of Seti I: “the finest tomb ever found.”

KV9 – Tomb of Ramses VI: astronomical ceiling artwork.

KV8 – Tomb of Merenptah.

KV11 – Tomb of Ramses III.

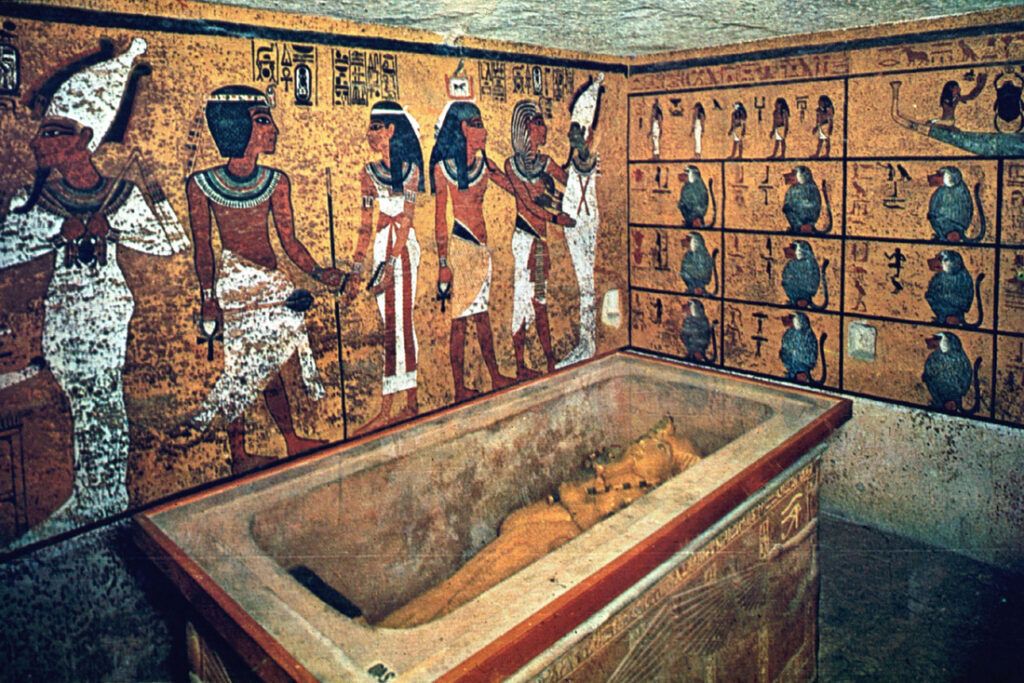

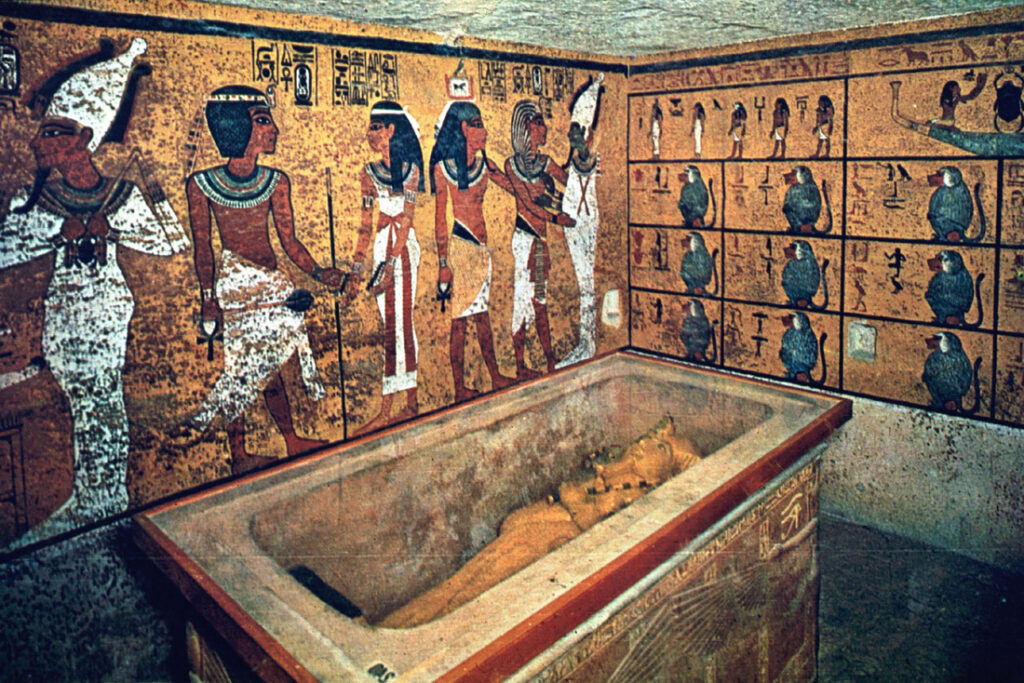

Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62)

The tomb of the Eighteenth Dynasty king Tutankhamun (c.1336–1327 BC) is world-famous because it is the only royal tomb from the Valley of the Kings that was discovered relatively intact. Its discovery in 1922 by Howard Carter made headlines worldwide, and continued to do so as the golden artifacts and other luxurious objects discovered in this tomb were being brought out. The tomb and its treasures are iconic of Egypt, and the discovery of the tomb is still considered one of the most important archaeological discoveries to date.

Despite the riches it contained, the tomb of Tutankhamun, number 62 in the Valley of the Kings, is in fact quite modest compared to the other tombs on this site, in both size and decoration. This is most likely due to Tutankhamun having come to the throne very young, and even then ruling for only around nine years in total. One can wonder at what riches the much larger tombs of the most powerful kings of the New Kingdom, such as Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, and Ramesses II once contained.

Only the walls of the burial chamber bear any decoration. Unlike most previous and later royal tombs, which are richly decorated with funerary texts like the Amduat or Book of Gates, which helped the deceased king reach the afterlife, only a single scene from the Amduat is represented in the tomb of Tutankhamun. The rest of the decoration of the tomb depicts either the funeral, or Tutankhamun in the company of various deities.

This small size of the tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62) has led to much speculation. When his successor, the high official Ay, died, he was buried in a tomb (KV23), which may have been originally intended for Tutankhamun, but which had not yet been completed at the time of the death of the young king. The same argument has been made in turn for the tomb of Ay’s successor, Horemheb (KV57). If so, it is unclear for whom the eventual tomb of Tutankhamun, KV62, was carved, but it has been argued that it existed already, either as a private tomb or as a storage area, that was subsequently enlarged to receive the king.

Whatever the reason, the small size of the tomb meant that the approximately 5000 artefacts that were discovered inside were stacked very tightly. These reflect the lifestyle of the royal palace, and included objects that Tutankhamun would have used in his daily life, such as clothes, jewelry, cosmetics, incense, furniture, chairs, toys, vessels made of a variety of materials, chariots, and weapons.

It is one of history’s great ironies that Tutankhamun, a relatively minor king who was erased from history because he was related to the unpopular King Akhenaten, has come to surpass many of Egypt’s greatest rulers in fame.

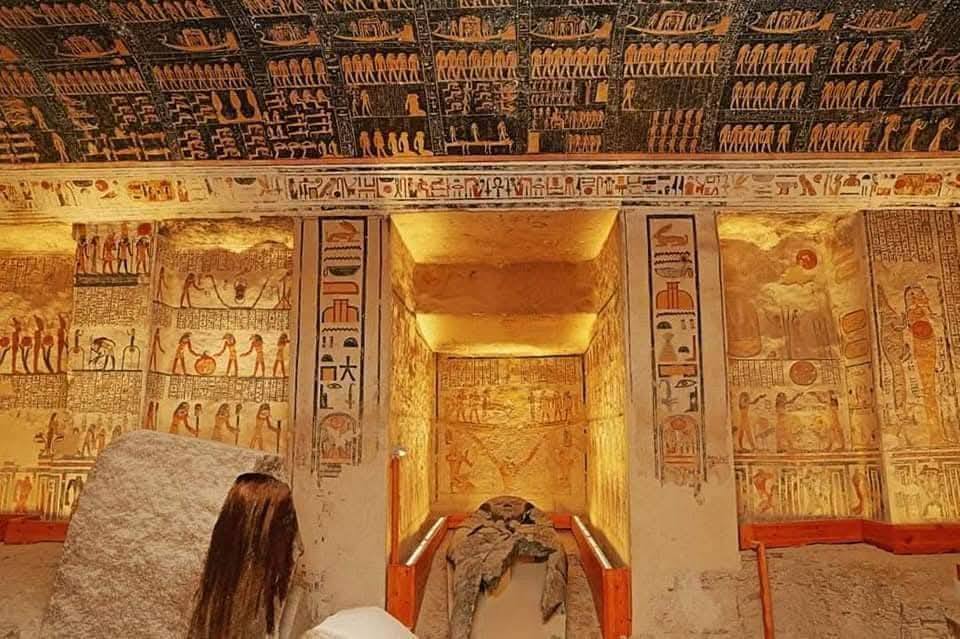

Tomb of Sety I (KV17)

The tomb of Sety I is one of the longest, deepest, and most beautifully decorated tombs in the The Valley of Pharaohs. Sety I (c.1294–1279 BC) was the second king of the Nineteenth Dynasty, and father of Ramesses II (the Great). His tomb, number 17 in the The Valley of Pharaohs, is sometimes called “Belzoni’s tomb” after its discoverer.

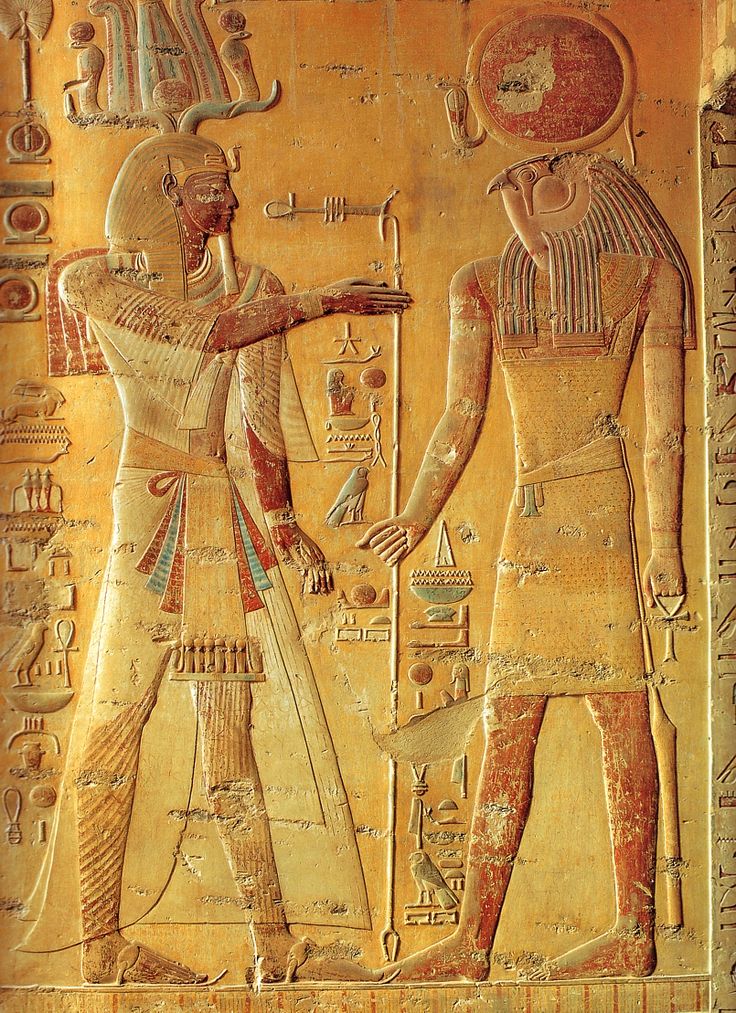

Like the other tombs in the Valley of the Kings, the tomb of Sety I is decorated with various funerary texts, the aim of which was to ensure his successful transition to the afterlife. The tomb of Sety I was the first tomb in the Valley of the Kings to be entirely decorated. The elegant painted scenes and reliefs are of the exquisite quality that the reign of Sety I is so well known for. The funerary texts attested there are the Litany of Re, Amduat, and Book of Gates, in addition to the Book of the Divine Cow and the gorgeous astronomical scenes decorating the ceiling of his burial chamber, simulating the night sky.

Architecturally, the tomb of Sety I falls under the “joggled axis” type characteristic of his period. The first series of corridors and descending passageways terminate into the first pillared room, where, in the facing wall, but off-axis, another series of descending passageways cut into the floor of the room lead to the burial chamber. The tomb does feature a number of new and unique characteristics. Along the same axis of the first series of corridors and descending passageways, a doorway leads into a single room. This may have been intended to lead intruders to believe that this was the actual burial chamber. The tomb of Sety I is also the first tomb to possess a burial chamber with a vaulted ceiling. Perhaps most interesting of all is that the passage begins on the floor of the burial chamber, descending even further, deep into the earth. It is believed that this was intended to ritually connect the tomb of Sety I with the primeval and regenerative powers of the underworld.

In 1821, painted recreations of several rooms from the tomb of Sety I were displayed in the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly in London. This exhibition, put together by the discoverer of the tomb, Giovanni Battista Belzoni, made an ancient Egyptian tomb available to various members of the public. It captured people’s imagination, and is one of the first monuments responsible for attracting popular attention to ancient Egypt.

Tomb of Ramesses VI (KV9)

This tomb was begun by King Ramesses V (c.1147–1143 BC) of the Twentieth Dynasty. Although it is uncertain whether he was ultimately buried here, it is clear that his uncle Ramesses VI (c.1143–1136 BC) enlarged the tomb and used it for his burial.

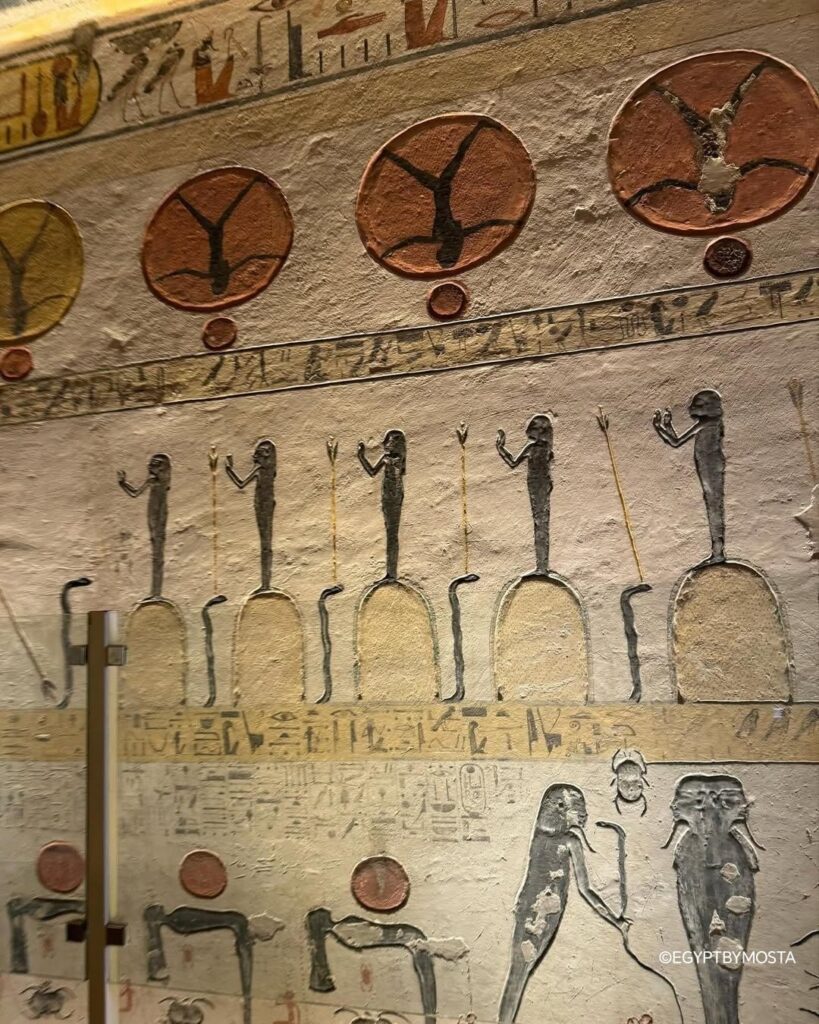

The tomb is simple in plan, essentially consisting of a series of descending corridors that lead deep underground, in a straight line to the burial chamber. The exquisitely painted sunk relief walls are very well preserved.

The tomb’s decorative programme consists of various funerary texts to help the king in his successful transition to the afterlife. The first descending passages are decorated with the Book of Gates, Book of Caverns, and Books of the Heavens, ancient Egyptian books of the afterlife. The passages beyond bear scenes from the Amduat, the Book of the Dead, and the Books of the Heavens, and scenes from the Book of the Earth adorn the burial chamber. All ceilings are decorated with astronomical scenes and texts. Some of these funerary texts are collections of spells, and others are maps of the underworld, describing the sun god’s daily nocturnal journey through it. Through them, just like the sun god, the king could achieve a glorious rebirth in the eastern horizon at dawn.

Tomb of Merenptah (KV8)

Mereneptah was the 11th son of King Ramses II and Queen Isis-Nofret. He was an old man and he ascended the throne after the long rule of his father. He ruled for only about ten years, but his tomb was completed before his death and only the rearmost chambers beyond the burial chamber were left undecorated and roughly cut. The Tomb of Merneptah is the second largest one in the Valley of the Kings, exceeded only by Tomb KV5.

Merenptah’s tomb became model for royal tombs at the decline of dynasties XIX and XX. The tomb design, although large, is simpler than that of Merenptah’s father and grandfather.

The tomb KV8 is one of many tombs in the Valley of the Kings that has been damaged by flash floods. Most of the tomb has been excavated, but the side chambers off the burial chamber are still full of debris, as are parts of the side chambers. The paint and plaster that survived the floods are in good condition. It was not until 1903 that the rear half of the tomb was excavated; and the Burial Chamber was not excavated until 1987.

Tomb of Ramses III (KV11)

It has been known since antiquity and was explored for the first time in the modern era in 1768 by James Bruce. The tomb was referred to as Tomb of the Harpists by Belzoni, who removed the lid and the sarcophagus. he used that name due to the bas-relief representation of two blind harpists. Meanwhile, the explorers from Europe named it Bruce’s tomb after James Bruce.

Located in the main valley of the Valley of the Kings, the tomb was originally started by Setnakhte, but abandoned when it broke into the earlier KV10 (tomb of Amenmesse). Setnakhte was buried in KV14. The tomb KV11 was restarted and extended and on a different axis for Ramesses III. The tomb was first mentioned by an English traveler Richard Pococke in the 1730s, but its first detailed description was given by James Bruce in 1768.

The Historical Significance of the Valley of Pharaohs

The Valley of Pharaohs, more widely known as the Valley of the Kings, holds a unique place in the history of Ancient Egypt. Unlike the iconic pyramids of Giza that tower above the desert sands, this sacred valley concealed the eternal resting places of Egypt’s most powerful rulers. For nearly 500 years, during the New Kingdom period (c. 1550–1069 BC), the Pharaohs, queens, and high-ranking nobles of Egypt chose this secluded desert landscape as the gateway to eternity.

The decision to build tombs in the Valley of Pharaohs marked a dramatic shift in royal burial practices. Earlier dynasties had constructed monumental pyramids that symbolized divine power but also attracted looters eager for treasure. By the time of the 18th Dynasty, Pharaohs realized that the grandeur of pyramids also made them vulnerable. A new strategy was born: tombs were carved deep into the limestone cliffs of western Thebes (modern Luxor), hidden from plain sight. Instead of massive structures visible for miles, the Valley of Pharaohs offered discreet entrances leading into intricate underground chambers.

The New Kingdom’s Golden Age

The Valley of Pharaohs became the stage upon which the New Kingdom’s greatest rulers scripted their legacy. This period was Egypt’s age of empire — Pharaohs expanded borders, amassed immense wealth, and built colossal temples such as Karnak and Luxor. But while temples glorified their power in life, their tombs in the Valley reflected their hopes for immortality.

Pharaohs like Thutmose I, Amenhotep III, Seti I, Ramses II, and Tutankhamun chose the Valley of Pharaohs as their eternal home. Each burial chamber was more than just a grave; it was a spiritual passageway designed to guide the soul safely through the perilous journey of the afterlife. Walls were covered in sacred texts, magical spells, and cosmic maps showing the Pharaoh’s voyage with the sun god Ra through the underworld before his rebirth at dawn.

The Religious and Cultural Significance

The Valley of Pharaohs was not selected by chance. The western bank of the Nile symbolized the land of the dead, where the sun disappeared each evening. This powerful symbolism made it the natural location for the Pharaohs’ tombs. Overlooking the valley is the natural pyramid-shaped peak of al-Qurn, a mountain considered sacred by the ancient Egyptians. It was seen as a natural guardian of the necropolis, echoing the earlier pyramid tradition but in a subtler, spiritual form.

A Chronicle of Power and Eternity

Today, the Valley of Pharaohs stands as a chronicle of one of the most remarkable chapters in human civilization. Each tomb is a silent testament to the Pharaoh’s vision of eternity, and together they tell the story of Egypt’s golden age of wealth, artistry, and spiritual devotion. Visiting the Valley is not just about exploring archaeology; it is about stepping into the world of kings who believed they were gods on earth and destined to live forever among the stars.

Tours to the Valley of Pharaohs from Hurghada

For many travelers to the Red Sea, a holiday in Hurghada is not complete without a journey back in time to explore the Valley of Pharaohs in Luxor. While Hurghada is famous for its beaches, diving, and luxury resorts, its true magic lies in how close it is to the treasures of Ancient Egypt. Just a few hours’ drive separates the turquoise waters of the Red Sea from the golden sands and sacred tombs of the Nile Valley. This makes day trips from Hurghada to Luxor one of the most sought-after experiences for visitors who dream of walking in the footsteps of the Pharaohs.

🚐 How to Get from Hurghada to the Valley of Pharaohs

The Valley of Pharaohs lies on the west bank of the Nile in Luxor, around 280 km from Hurghada. Travelers can choose between several options:

Day trip by coach or minibus: The most popular choice, taking around 4–5 hours each way. Comfortable buses or air-conditioned minibuses pick you up from your hotel in Hurghada and bring you directly to Luxor.

Private car tours: Ideal for families, couples, or small groups who want flexibility and privacy. You can travel at your own pace, stop for photos, and enjoy personalized guidance.

Luxor by flight from Hurghada: Though less common, domestic flights can shorten travel time dramatically, but most visitors opt for the scenic road trip through the desert and along the Nile Valley.

No matter the route, the anticipation builds as you leave the Red Sea coast behind and approach the green fields of the Nile, where Ancient Egypt’s greatest monuments await.

🏛️ Typical Tour Itinerary

A day trip to Luxor from Hurghada usually follows a well-planned schedule to ensure you see the highlights:

Early morning departure from Hurghada.

Arrival in Luxor and a visit to the Karnak Temple Complex, the largest religious site in the world.

Lunch at a local restaurant overlooking the Nile.

Afternoon crossing to the West Bank of the Nile to explore the Valley of Pharaohs (Valley of the Kings). Here, you can step inside several tombs, marvel at the artwork, and feel the atmosphere of eternity.

Visit to the Temple of Queen Hatshepsut, one of Egypt’s most remarkable female rulers.

Stop at the Colossi of Memnon, two gigantic statues that once guarded a lost temple.

Return journey to Hurghada in the evening.

This itinerary allows you to explore the wonders of Luxor in just one day while focusing on the Valley of Pharaohs, the crown jewel of the west bank.

🎤 Why Book with an Egyptologist Guide

Exploring the Valley of Pharaohs with a professional Egyptologist transforms the trip from a sightseeing tour into a journey of discovery. The guide explains the meaning of the hieroglyphs, the myths of the underworld, and the personal stories of Pharaohs like Ramses II, Seti I, and Tutankhamun. Every painting on the tomb walls comes alive when you understand its significance.

🌟 Why Choose HurghadaToGo for Your Valley of Pharaohs Tour

Expert planning: We create itineraries that maximize your time in Luxor.

Comfortable transfers: Air-conditioned vehicles with professional drivers.

Licensed guides: Knowledgeable Egyptologists fluent in multiple languages.

Personalized service: Options for group, small-group, or private tours.

Trust & reliability: Hundreds of satisfied travelers recommend HurghadaToGo for making their Egyptian adventure unforgettable.

🕰️ Best Time to Visit

Tours from Hurghada to the Valley of Pharaohs run year-round, but the most comfortable months are October to April when temperatures are cooler. If you visit in summer, early morning departures ensure you explore the tombs before midday heat sets in.

Easy & Secure Booking

Reserve your unforgettable Hurghada to Sharm El Luli Day Trip 2026 now through:

🌐 Official Website: hurghadatogo.com

📧 Email: [email protected]

📱 WhatsApp: +201009255585

( For quick personalized assistance WhatsApp Chat )

We also recommend you :