Ancient Egypt: A Civilization of Power, Belief, and Legacy

Few civilizations in history have left such a lasting impression as ancient Egypt. For thousands of years, the banks of the Nile nurtured a society of extraordinary rulers, skilled artisans, innovative farmers, and devoted priests. From its monumental pyramids to its intricate belief systems, ancient Egypt continues to fascinate scholars and travelers alike. In this blog post, we will journey through its government, daily life, religion, and enduring cultural legacy.

The Nile: Lifeline of Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, geography was destiny. The Nile River was the beating heart of the civilization, flooding each year and leaving behind fertile soil that supported abundant harvests. Without the Nile’s predictable rhythms, ancient Egypt could never have sustained such a large and powerful population. The deserts to the east and west protected the land from many invasions, while also shaping the resilience and independence of its people.

Agriculture and Daily Life in Ancient Egypt

Life in ancient Egypt revolved around the land and the river. Farming was the backbone of society, with wheat, barley, vegetables, and flax cultivated in the fertile Nile Valley. Farmers used simple but effective irrigation techniques to channel water to their fields, ensuring stability even in years of low flooding.

Animals were equally important. Cattle, goats, and sheep provided food, milk, and hides, while donkeys were essential for transport. Fishing and hunting added variety to the Egyptian diet. Villages dotted the landscape, their mud-brick homes clustered near the fields.

Daily life in ancient Egypt was family-centered. Women played active roles, managing households and sometimes even property, while men worked the land or learned skilled trades. Children were raised to follow in their parents’ footsteps, though education for scribes opened paths to social mobility.

Society, Population, and Class Structure

The society of ancient Egypt was carefully layered yet surprisingly flexible. At the top stood the pharaoh, seen not only as a king but as a divine figure responsible for maintaining cosmic order, or ma’at. Supporting him were priests, nobles, and officials who ensured that laws and taxes were enforced.

Below them were scribes, artisans, and soldiers — respected professions that contributed to Egypt’s wealth and stability. Most people, however, were farmers, bound to the land but essential to the kingdom’s survival. While slavery did exist, it was not the dominant labor system; many workers were peasants or dependents tied to estates rather than slaves in the strict sense.

Despite this hierarchy, ancient Egypt allowed for some mobility. Foreigners could rise through military service, and skilled individuals could improve their status, especially if they adopted Egyptian customs and language.

Art, Architecture, and Technology

The breathtaking monuments of ancient Egypt are some of the most iconic structures in the world. The Great Pyramids of Giza, colossal temples of Karnak and Luxor, and the richly decorated tombs of the Valley of the Kings all reveal the Egyptians’ mastery of stone and their devotion to the afterlife.

Art in ancient Egypt was not simply decorative — it was deeply symbolic. Statues, reliefs, and paintings followed strict conventions meant to express eternal truths rather than fleeting moments. Jewelry, pottery, and household items combined functionality with exquisite craftsmanship.

Technology advanced steadily: quarrying stone, transporting massive blocks, and aligning structures with astronomical precision required extraordinary knowledge. The innovations of ancient Egypt still puzzle engineers today, standing as testaments to human ingenuity.

Religion, Kingship, and the Afterlife

Religion in ancient Egypt was not just a matter of temples and priests — it was the heartbeat of society. Every sunrise and harvest was seen as a gift from the gods, and every drought or misfortune as a sign that order had been disturbed. Egyptians lived with the constant awareness of the divine, weaving spirituality into farming, family, law, and even politics.

The pharaoh embodied this connection between people and the divine. As “Son of Ra,” he was believed to be a living god who ruled with absolute authority, yet with immense responsibility. Maintaining ma’at — the balance between chaos and order — was his sacred duty. This idea justified not only the pharaoh’s political power but also the massive resources invested in temples, rituals, and building projects.

Temples in ancient Egypt were more than places of worship. They were centers of learning, storage for surplus food, hubs of economic exchange, and employers of countless workers. A temple could own land, command laborers, and operate almost like a miniature kingdom within the state. Priests, trained in sacred rituals, ensured that offerings and ceremonies were performed daily, sustaining the gods and, by extension, the stability of the world.

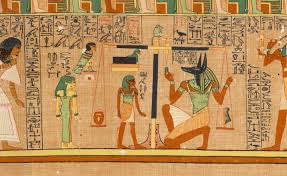

The afterlife was a central obsession. Egyptians believed that death was a passage to another world, where the soul would be judged in the Hall of Osiris. The famous “Weighing of the Heart” determined whether one’s soul was pure enough to join the eternal fields of paradise. This belief explains the elaborate process of mummification, the construction of tombs, and the texts like the Book of the Dead buried with the deceased. For the people of ancient Egypt, death was not to be feared but prepared for — a journey requiring both material goods and spiritual readiness.

Writing, Knowledge, and Administration

The genius of ancient Egypt can also be measured in its systems of knowledge and governance. At the heart of it was writing. Hieroglyphs, the striking script of sacred carvings, were not just symbols but a complex system combining sounds, ideas, and artistry. These inscriptions adorned temples, recorded royal achievements, and connected the king with divine forces.

For everyday purposes, scribes relied on simpler scripts: hieratic and later demotic. On papyrus scrolls, ostraca (pottery shards), and wooden tablets, they documented contracts, legal cases, tax rolls, and personal letters. This vast web of record-keeping made it possible for the pharaohs to control resources and direct labor on a scale unmatched by many other civilizations.

Scribes were among the most respected figures in ancient Egypt. They enjoyed privileges denied to most farmers and laborers, since literacy was a rare skill. Becoming a scribe required years of training, but it opened the door to positions in government, temples, and commerce. Egyptian wisdom literature even advised parents to encourage their sons to pursue writing, praising it as a path to stability and prosperity.

Knowledge extended beyond administration. Medical papyri reveal treatments for wounds, fevers, and digestive issues, often mixing herbal remedies with spiritual incantations. Astronomical observations allowed priests to track the stars and create calendars that guided agricultural life. Mathematics, too, played a vital role: Egyptians mastered geometry for measuring fields, designing temples, and building pyramids with extraordinary accuracy.

The administration of ancient Egypt was both sophisticated and deeply human. Records show disputes over land boundaries, complaints about corrupt officials, and even letters from workers demanding overdue wages. Far from being a faceless bureaucracy, the Egyptian state was a living system, balancing authority with the daily needs of its people.

Historical Periods of Ancient Egypt

The history of ancient Egypt is best understood as a story of cycles: times of unity and strength followed by fragmentation and renewal. Each major period contributed something essential to the civilization’s character.

Predynastic and Early Dynastic Periods (before 2600 BCE): Long before the pyramids, communities along the Nile began to unify. Kings of Upper and Lower Egypt merged their realms, creating the “Two Lands” under a single crown. This period saw the first hieroglyphs, early temples, and the establishment of royal burials that set the stage for later grandeur.

Old Kingdom (c. 2543–2120 BCE): Known as the Age of the Pyramids, this era produced Egypt’s most iconic monuments. Pharaohs like Djoser, Khufu, and Sneferu commissioned massive projects, pushing engineering to new heights. The Old Kingdom also established the ideology of kingship — that the pharaoh was both ruler and god, responsible for prosperity and order. However, the enormous cost of these projects, combined with weak leadership toward the end, led to a decline known as the First Intermediate Period.

Middle Kingdom (c. 1938–1630 BCE): Stability returned under powerful rulers like Mentuhotep II. The Middle Kingdom emphasized cultural flourishing: literature blossomed with tales and wisdom texts, while art and architecture reflected both grandeur and humanity. Pharaohs expanded Egypt’s reach into Nubia, securing resources like gold and exotic goods. Yet pressures from internal challenges and foreign groups eventually brought instability once again.

New Kingdom (c. 1539–1077 BCE): This was the golden age of ancient Egypt. Pharaohs like Hatshepsut expanded trade networks, Akhenaten introduced radical religious reforms, Tutankhamun restored tradition, and Ramses II secured military glory. Monumental temples like Karnak and Abu Simbel were built, and Egypt projected its power across the Near East. This period also produced some of the most vivid art and inscriptions, leaving behind a rich record of life and belief.

Late Period (c. 664–332 BCE): Though marked by foreign invasions, including Assyrian and Persian control, this era showed Egypt’s resilience. Temples continued to be built, art and religion remained vibrant, and Egyptians adapted to changing rulers while preserving their traditions. The arrival of Alexander the Great in 332 BCE ended pharaonic rule but also began a new chapter under the Ptolemies, blending Greek and Egyptian cultures.

Despite its ups and downs, the story of ancient Egypt is one of remarkable continuity. Across millennia, Egyptians held fast to their identity, their gods, and their vision of the afterlife, leaving a legacy that endures to this day.

Ancient Egypt: A Civilization of Power

The Ptolemaic Dynasty: A Legacy of Exploitation and Grandeur in Hellenistic Egypt

Introduction: The Dawn of a New Era

The death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE triggered a massive power struggle among his ambitious generals, known as the Diadochi. From this fractious conflict, one of his most trusted companions, Ptolemy, son of Lagus, secured for himself the richest prize of the empire: the ancient land of Egypt. Thus began the Ptolemaic Dynasty, a three-century-long rule that would profoundly transform Egypt’s government, economy, and society. The Ptolemies established a uniquely dualistic state, presenting themselves as traditional pharaohs to the native Egyptian populace while governing as absolute Hellenistic monarchs from the gleaming, newly-founded capital of Alexandria. This period was characterized by immense wealth, cultural brilliance, and a highly sophisticated, yet brutally exploitative, administrative machine designed to extract Egypt’s vast resources for the benefit of the Greek ruling class.

The Architecture of Power: A Centralized Bureaucratic State

The Ptolemaic system of government was remarkable for its level of centralization and bureaucratic intrusion into every aspect of economic life. Unlike the relatively loose feudal-style structures of earlier pharaonic periods, the Ptolemies established a regime where the state was the dominant economic actor.

The Monarch as Pharaoh and King: The Ptolemies mastered the art of political theater. To the native Egyptians, they were the divine pharaohs, heirs to the legacy of Ramses II and Thutmose III. They were depicted in traditional regalia on temple walls, participated in religious ceremonies, and funded the construction of magnificent temples like Edfu and Dendera, thereby gaining the legitimizing support of the powerful priesthood. However, within the court and administration in Alexandria, they ruled as absolute Greek kings. The state was treated as their personal estate (oikos), and its primary function was to enrich the royal house.

The Intricate Bureaucracy: The efficiency of this exploitation was made possible by an army of scribes and officials operating from the capital down to the smallest village. Every person, animal, and arura of land was registered. Detailed records were kept of harvests, livestock, and artisanal production. This bureaucracy was primarily staffed by Greek-speaking Macedonians and other immigrants, creating a linguistic and ethnic barrier to high office for native Egyptians. Key positions included the Dioiketes, the powerful finance minister, and the Strategos, the military governor of each region (nome).

Economic Domination: The System of State Monopolies

The true engine of Ptolemaic wealth was the system of state monopolies and controlled production. The government did not simply tax private enterprise; it actively owned and managed the most profitable sectors of the economy.

The Grain Monopoly: As the breadbasket of the Mediterranean, Egypt’s agricultural wealth was paramount. The state claimed ownership of all land. Peasant farmers, who were effectively tied to their land, were forced to cultivate a certain portion with grain (primarily wheat). They were required to surrender a significant portion of their harvest as tax-in-kind to state granaries. This grain was then exported throughout the Mediterranean, generating enormous profits for the royal treasury and funding the Ptolemies’ foreign wars and lavish court.

Other Key Monopolies:

Papyrus: The Nile Delta produced the ancient world’s primary writing material. The state controlled its harvesting and processing, creating a valuable export commodity.

Oil Production: The crushing of oils from linseed, castor, and sesame plants was a state monopoly. Farmers were compelled to sell their seeds to state-run factories, and consumers had to purchase oil from licensed retailers at fixed prices.

Banking and Coinage: The Ptolemies introduced a closed monetary system based on silver and bronze coinage. Taxes had to be paid in coin, which forced the barter-based Egyptian economy into the cash system, further facilitating taxation and control.

Social Stratification and Daily Life under the Ptolemies

Ptolemaic society was rigidly stratified along ethnic lines, creating a clear hierarchy that privileged the Greek minority and marginalized the native Egyptian majority.

The Ruling Elite: At the top were the Macedonian Greeks, who filled the highest ranks of the administration, army, and court. A key institution was the kleruchy system, whereby Greek soldiers were granted plots of land (kleroi) in return for military service. This created a loyal, permanent class of soldier-settlers dispersed throughout the country.

The Middle Strata: Some educated Egyptians who learned Greek (Hellenized) could find employment in the lower echelons of the bureaucracy. The native Egyptian priesthood also maintained significant influence and wealth, as the Ptolemies carefully cultivated their support with donations and temple-building projects.

The Exploited Majority: The vast majority of the population—native Egyptian peasants, laborers, and artisans—bore the full weight of the Ptolemaic system. They faced heavy taxes, compulsory labor on irrigation projects (corvée), and had little recourse against the demands of the Greek-speaking officials. Their lives were one of subsistence, with the constant threat of famine if the state’s tax demands left insufficient food.

Cultural Synthesis and Conflict

The relationship between the Greek ruling class and the native Egyptian population was complex. While there was some cultural exchange, particularly in religion (e.g., the syncretic god Serapis), the two societies largely remained separate. Intermarriage was uncommon among the elite, and Alexandria was a distinctively Greek polis on the coast, while the Egyptian countryside (chora) retained its traditional character.

This systemic exploitation inevitably led to tension and revolt. Throughout the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, as the royal family became embroiled in destructive dynastic feuds (the Syrian Wars), native Egyptian rebellions became increasingly common and severe. The Thebaid region in the south was a particular hotbed of unrest, at times even establishing independent, native-ruled states for short periods.

Conclusion: The Ptolemaic Legacy and the Roman Transition

The Ptolemaic Dynasty ended as it began: with a power struggle following the death of its most famous ruler, Cleopatra VII. Her defeat by Octavian (the future Emperor Augustus) at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE marked the end of Egyptian independence and the beginning of Roman rule.

The Ptolemaic legacy is a study in contrasts. It was an era of unparalleled cultural achievement, centered on the Museum and Library of Alexandria, which made the city the intellectual capital of the world. Yet, this golden age was built on the back of a ruthlessly efficient system of economic exploitation that widened the gap between ruler and ruled. The Romans, pragmatic administrators that they were, would essentially inherit and maintain the Ptolemaic bureaucratic apparatus, recognizing it as a supremely effective method for extracting the wealth of Egypt, now to be directed to the treasury in Rome.