Pyramids of Giza: Wonders of Ancient Egypt and UNESCO World Heritage

7 Fascinating Facts About the Pyramids of Giza: Wonders of Ancient Egypt

The oldest of the Seven Wonders of the World Pyramids of Giza, Egypt.

The Pyramids of Giza, built during Egypt’s 4th Dynasty (around 2575–2465 BCE), rise majestically from the rocky plateau on the west bank of the Nile near modern-day Giza. In the world of ancient Egypt, these monumental structures stood as symbols of royal power and divine belief, so awe-inspiring that they were later counted among the Seven Wonders of the World. Today, the entire Memphis area — including the Pyramids of Giza along with the necropolises of Saqqara, Dahshur, Abu Ruwaysh, and Abu Sir — is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, designated in 1979 for its unmatched cultural legacy.

Top 10 Secrets of the Pyramids of Giza: Ancient Egypt’s Greatest Wonders

The three great pyramids of Giza are named after the kings they were built for — Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure. The northernmost and oldest is the Great Pyramid of Khufu (known to the Greeks as Cheops), the second ruler of Egypt’s 4th Dynasty. This colossal structure is the largest of the group, with each side of its base originally measuring about 755 feet (230 meters) and rising to a height of 481 feet (147 meters).

To the south stands the pyramid of Khafre (Chephren), the fourth king of the dynasty. Slightly smaller than Khufu’s, it originally rose 471 feet (143 meters) high, with sides measuring about 707 feet (216 meters). The third and smallest of the trio belongs to Menkaure (Mykerinus), the fifth king of the 4th Dynasty. Its base measures about 356 feet (109 meters) per side, and it once stood 218 feet (66 meters) tall.

Over the centuries, all three pyramids were stripped of their smooth white limestone casings and robbed of their original treasures. Today, the Great Pyramid stands at 451 feet (138 meters), its outer casing long gone, while Khafre’s pyramid still retains a small section of limestone near its peak.

Each pyramid was part of a larger funerary complex. Mortuary temples were built beside them, connected by long causeways to valley temples near the Nile floodplain. Smaller subsidiary pyramids nearby housed the burials of royal family members, reflecting the deep connection between kingship, religion, and the afterlife in ancient Egypt.

The Ultimate Guide to the Pyramids of Giza: 5,000 Years of Ancient Egypt

Khufu’s pyramid, better known as the Great Pyramid of Giza, is often considered the most extraordinary single building ever constructed on Earth. Rising at a precise angle of 51°52′ and perfectly aligned with the four cardinal points, it showcases the remarkable knowledge of mathematics and astronomy in ancient Egypt.

The structure’s core was built from yellow limestone blocks, while its original gleaming white casing and inner passages were crafted from finer limestone. At its heart lies the burial chamber, constructed from massive granite blocks transported from quarries far to the south.

In total, around 2.3 million blocks of stone — weighing an estimated 5.75 million tons — were cut, hauled, and fitted together to form this monumental tomb. The precision of its construction is breathtaking: the joints between blocks, both in the interior walls and the surviving outer casing, are finer than anything else produced in ancient Egyptian masonry. The Great Pyramid is not only a royal monument but also a timeless masterpiece of engineering and human determination.

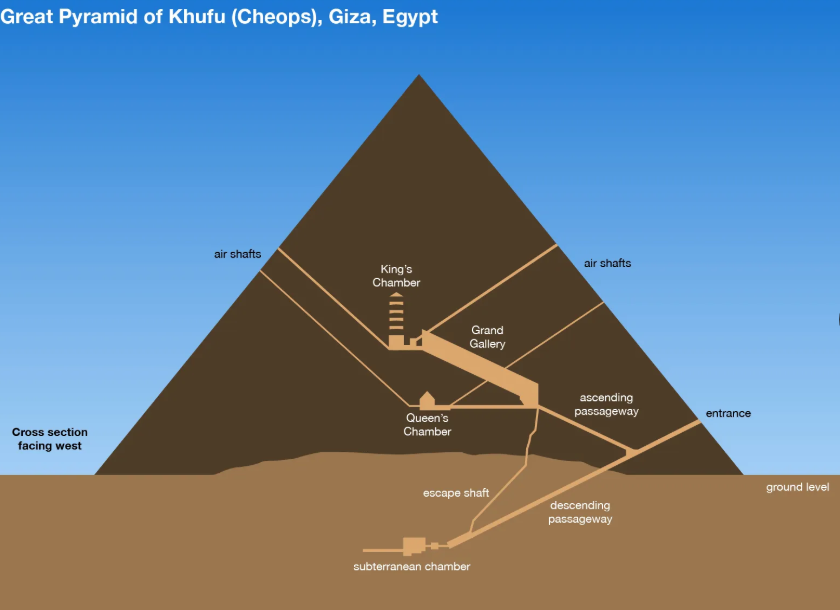

The Great Pyramid of Giza, one of the crowning achievements of ancient Egypt, conceals a fascinating interior design as impressive as its monumental exterior. The entrance lies on the north face, about 59 feet (18 meters) above the ground. From here, a sloping corridor descends through the pyramid’s stonework, cuts into the bedrock beneath, and ends in an unfinished subterranean chamber.

Branching off this passage is an ascending corridor that leads to the so-called Queen’s Chamber and to the Grand Gallery — a striking slanted hall stretching 151 feet (46 meters) long. From the gallery’s upper end, a narrow passage continues into the King’s Chamber, the true burial chamber of Khufu. This room, entirely lined and roofed with granite, reflects the immense effort and precision that defined pyramid construction in ancient Egypt.

Two small shafts extend from the King’s Chamber, angling outward to the exterior of the pyramid. Scholars debate their purpose: some believe they were symbolic passages for the king’s soul to ascend to the heavens, while others suggest they were for ventilation. Above the chamber are five relieving compartments, each separated by massive granite blocks, designed to distribute the immense weight of masonry and protect the chamber below.

The combination of engineering ingenuity and spiritual symbolism makes the pyramid’s interior a true marvel of ancient Egyptian architecture.

The mystery of how the pyramids were built has fascinated scholars and travelers for centuries, and even today there is no single, fully conclusive answer. The most widely accepted theory suggests that the builders of ancient Egypt used massive sloping ramps made of brick, earth, and sand. As the pyramid grew taller, the ramps were extended in both height and length, allowing workers to haul stone blocks upward using sledges, rollers, and levers.

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus claimed that the Great Pyramid took 20 years to complete and required the labor of 100,000 men. This number seems plausible if we consider that many of these workers were farmers who joined construction crews during the annual Nile flood, when agricultural work was impossible.

Modern archaeology, however, paints a slightly different picture. Excavations at Giza have uncovered workers’ villages, bakeries, and medical facilities, suggesting that a smaller but permanent workforce lived on-site year-round. Current estimates propose that around 20,000 laborers — supported by bakers, physicians, priests, and other specialists — could have been sufficient to build the Great Pyramid.

This combination of human organization, technical ingenuity, and sheer determination demonstrates why the pyramids remain one of the most enduring achievements of ancient Egypt.

South of the Great Pyramid, near the valley temple of Khafre, stands one of the most iconic monuments of ancient Egypt — the Great Sphinx. Carved directly from the limestone bedrock, the Sphinx combines the body of a reclining lion with the face of a man, symbolizing strength, wisdom, and royal power. Measuring about 240 feet (73 meters) in length and 66 feet (20 meters) in height, this colossal guardian has inspired awe for millennia and continues to spark debate about its exact origins and purpose.

Another remarkable discovery near Khufu’s pyramid sheds light on royal life during the 4th Dynasty. In 1925, archaeologists uncovered a shaft tomb containing the burial equipment of Queen Hetepheres, Khufu’s mother. Though her sarcophagus was found empty, the chamber was filled with exquisite treasures — furniture, jewelry, and ceremonial objects — all testifying to the extraordinary craftsmanship of the artisans of ancient Egypt. These finds remind us that the pyramids were not only monuments of stone but also repositories of artistry, symbolism, and devotion to the afterlife.

Surrounding the three great pyramids is a vast necropolis filled with flat-roofed tombs known as mastabas. These rectangular structures, arranged in an orderly grid, served as the burial places for royal relatives, nobles, and high officials who wished to rest close to their kings. The mastabas of the 4th Dynasty form the core of the cemetery, but archaeologists have also uncovered many more from the 5th and 6th Dynasties (c. 2465–2150 BCE), built among and around the earlier tombs.

Together, the pyramids and mastabas create a sprawling funerary landscape that reflects the social and political order of ancient Egypt — a place where pharaohs, priests, and administrators sought eternal life in the shadow of the pyramids.

Excavations around the pyramids in the late 1980s and 1990s uncovered fascinating evidence of the people who built these wonders of ancient Egypt. Archaeologists discovered entire workers’ districts, complete with bakeries, storage facilities, and workshops, revealing a bustling community that supported the massive construction efforts.

Nearby, they also found the modest tombs of laborers and artisans. These ranged from simple mud-brick domes to more elaborate stone structures, reflecting the varying status of the workers. Inside some tombs, archaeologists uncovered statuettes and personal items, while hieroglyphic inscriptions on the walls occasionally revealed the names of the deceased.

These discoveries remind us that behind the grandeur of the pyramids stood thousands of skilled and dedicated individuals whose lives were closely tied to the monumental legacy of ancient Egypt.

The Pyramids of Giza and the Great Sphinx are not only among the most famous landmarks of ancient Egypt, but also some of the most visited tourist attractions in the world. Their fame stretches back thousands of years — even the Romans considered them must-see wonders. Built during the 4th Dynasty (c. 2613–2494 BCE), these monumental structures were created as eternal tombs for kings. The Great Pyramid of Khufu (c. 2589–2566 BCE) is the oldest and largest, followed by the pyramids of his son, Khafre, and his grandson, Menkaure. Remarkably, Khufu’s Great Pyramid held the record as the tallest building in the world for nearly 3,800 years.

Yet the three pyramids are only part of the story. Each royal pyramid was the centerpiece of a much larger funerary complex. Surrounding them were smaller queens’ pyramids, satellite pyramids that symbolically served the king, mastaba tombs for nobles and family members, and even burials of boats — some real, others symbolic — meant to carry the pharaoh into the afterlife.

Two temples also formed key elements of each complex. The valley temple, built near water, served as the entry point where boats could dock. From there, a decorated causeway led to the funerary temple, located near the pyramid’s base. Here, priests carried out daily rituals, offering food, drink, and goods to sustain the king’s soul in the afterlife. These ceremonies reflected the deeply spiritual nature of ancient Egypt, where kingship was tied not only to earthly power but also to divine eternity.

The monuments of Giza are, therefore, far more than stone tombs — they are living reminders of the religious devotion, architectural genius, and cultural legacy of ancient Egypt.

The Great Pyramid of Giza: Ancient Egypt’s Timeless Wonder

The Great Pyramid of Giza is more than just a monument — it is one of humanity’s greatest architectural achievements and a lasting symbol of the power and mystery of ancient Egypt. Built over 4,500 years ago during the reign of Pharaoh Khufu (c. 2589–2566 BCE), it remains the largest and oldest of the three pyramids on the Giza Plateau. For nearly 3,800 years, no man-made structure on Earth surpassed its height, making it one of the most enduring symbols of human ingenuity.

A Monument of Immense Scale

The Great Pyramid of Giza originally stood at 481 feet (147 meters) tall, with each side measuring about 755 feet (230 meters). Constructed with an estimated 2.3 million limestone and granite blocks weighing up to several tons each, it has a total mass of around 5.75 million tons. Even today, with much of its smooth white limestone casing gone, the pyramid rises an impressive 451 feet (138 meters).

Its precise alignment to the four cardinal points and its perfect geometric proportions reveal the extraordinary skills of the engineers of ancient Egypt. Many experts believe massive ramps, sledges, and levers were used to transport and position the blocks, though the exact methods remain a mystery.

Inside the Great Pyramid of Giza

The interior of the Great Pyramid of Giza is just as fascinating as its imposing exterior. The entrance lies on the north face, leading into a series of passageways. These include the descending corridor, the Queen’s Chamber, the Grand Gallery, and finally the King’s Chamber — a granite-lined room that once housed Khufu’s sarcophagus. Above it, massive granite blocks were arranged to distribute the immense weight of stone above, protecting the chamber from collapse.

Two narrow shafts extend from the King’s Chamber toward the exterior. Scholars debate their purpose: were they for ventilation, or symbolic pathways to the stars, guiding the pharaoh’s soul into eternity?

Builders and Workforce

For centuries, stories of slaves building the pyramids dominated popular imagination. Modern archaeology, however, paints a different picture. Excavations around the site uncovered workers’ villages complete with bakeries, workshops, and even medical facilities. Evidence suggests that a permanent workforce of around 20,000 skilled laborers, supported by bakers, physicians, and priests, constructed the pyramid — a testament to the organization and community of ancient Egypt.

Cultural and Religious Significance

The Great Pyramid of Giza was far more than a tomb. For the people of ancient Egypt, it was a sacred symbol of kingship, eternity, and divine order. Its towering shape represented the primordial mound of creation and the rays of the sun, linking Pharaoh Khufu to the gods. Daily rituals in the adjacent temples ensured the pharaoh’s soul would thrive in the afterlife, reinforcing the Egyptian belief that death was not an end but a transformation.

The Great Pyramid of Giza Today

Today, the Great Pyramid of Giza continues to inspire millions of visitors each year. Recognized as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World — and the only one still standing — it stands as a reminder of the brilliance of ancient Egypt. Tourists can explore the plateau, marvel at the nearby pyramids of Khafre and Menkaure, and gaze upon the enigmatic Great Sphinx, which guards the complex.

The monument’s survival through thousands of years of history — from pharaohs to Romans, and now into the modern era — makes it one of the most remarkable testaments to human civilization.

Conclusion

The Great Pyramid of Giza is not only the crown jewel of ancient Egypt but also one of the greatest wonders in world history. From its colossal scale and intricate design to its spiritual symbolism and enduring legacy, it continues to fascinate historians, archaeologists, and travelers alike. A journey to the Giza Plateau is not just a trip to a tourist site — it is a step back in time, into the heart of a civilization whose mysteries still echo through the desert winds.