Medinet Habu: Egypt’s Hidden Gem of the New Kingdom

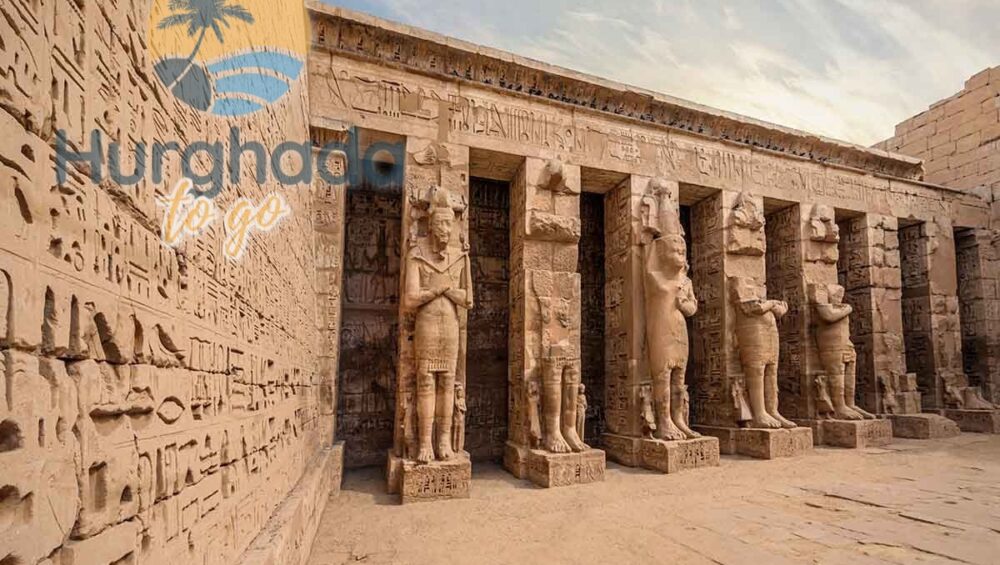

Nestled on the West Bank of the Nile in Luxor, Medinet Habu is one of Egypt’s most captivating yet under-visited archaeological treasures. Known for its stunningly preserved mortuary temple of Ramesses III, this ancient complex from the New Kingdom (circa 1186–1155 BCE) offers a vivid window into pharaonic history, art, and architecture. Whether you’re a history enthusiast or a traveler seeking an authentic experience, Medinet Habu is a must-see destination that rivals the grandeur of Karnak and the Valley of the Kings.

A Monument to Ramesses III

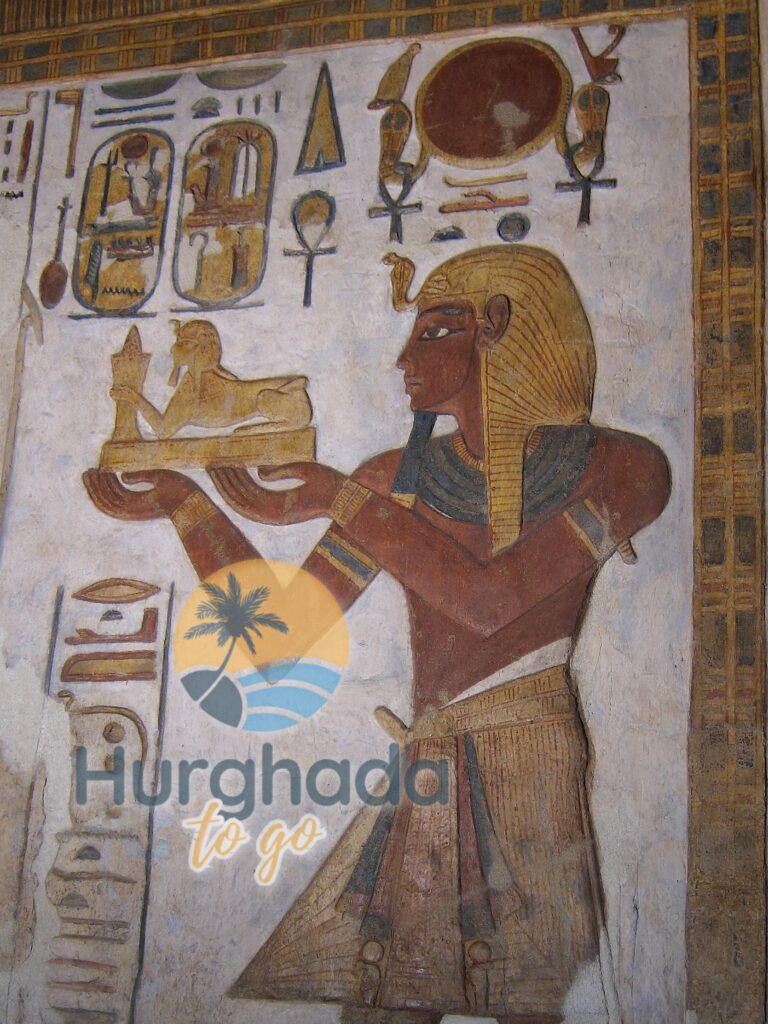

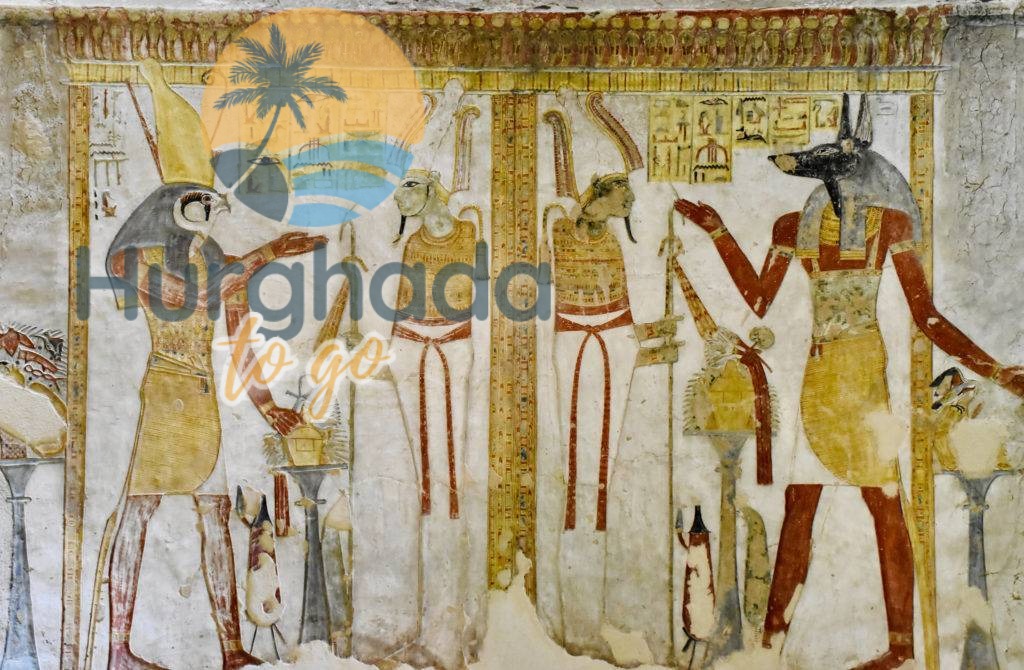

The heart of Medinet Habu is the grand mortuary temple built by Ramesses III, the second pharaoh of the 20th Dynasty and one of Egypt’s last great warrior-kings. Dedicated to Amun-Re and the deified Ramesses III, the temple served as both a religious sanctuary and a fortified administrative hub. Its towering pylons and vibrant reliefs narrate the pharaoh’s triumphs over invaders like the Sea Peoples, Libyans, and Nubians. These intricate carvings, many retaining their original colors, make Medinet Habu a masterpiece of ancient Egyptian storytelling.

Unlike the crowded sites of Luxor, Medinet Habu offers a serene experience, allowing visitors to immerse themselves in its detailed scenes of battles, festivals, and royal processions. The temple’s First Pylon, with its imposing gateway, and the hypostyle halls filled with colossal columns are architectural marvels that transport you back to the New Kingdom’s peak.

The Medinet Habu King List: A Royal Procession

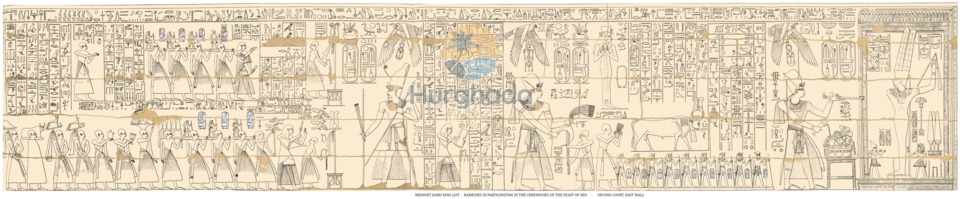

One of the highlights of Medinet Habu is the Medinet Habu King List, located in the second courtyard. Carved during the Festival of Min, this procession depicts Ramesses III honoring his deified predecessors through 16 cartouches. The list includes iconic pharaohs from the 18th and 19th Dynasties, such as Ahmose I (founder of the New Kingdom), Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, Seti I, and Ramesses II. This veneration of ancestral kings underscores Ramesses III’s claim to divine legitimacy and connects Medinet Habu to other royal canons, like those at Abydos and Karnak.

The vivid colors and detailed craftsmanship of the king list make it a standout feature, offering a rare glimpse into how ancient Egyptians celebrated their rulers’ legacies.

Beyond Ramesses III: Layers of History

While Medinet Habu is synonymous with Ramesses III, its history spans multiple dynasties. The site includes an earlier temple from the 11th Dynasty, dedicated to the Ogdoad deities, which was later expanded by Hatshepsut and Thutmose III into a shrine for Amun. Nearby, a memorial temple originally built by Ay was later usurped by Horemheb, both from the 18th Dynasty. These layers of construction reveal Medinet Habu as a living site, evolving through centuries of pharaonic rule.

In the post-pharaonic era, Medinet Habu became a Coptic settlement, with churches built within its walls. Today, as a UNESCO World Heritage site, it stands as a testament to Egypt’s enduring cultural and religious significance.

Ramesses III: The Last Great Warrior Pharaoh

Ramesses III (reigned c. 1186–1155 BCE) was the second pharaoh of Egypt’s 20th Dynasty during the New Kingdom, often regarded as the last great ruler of this era. His reign marked a period of resilience amid economic decline, invasions, and internal strife, earning him a legacy as a formidable warrior, builder, and administrator. Below is a detailed overview of his life, achievements, and significance, with a focus on his connection to Medinet Habu.

Key Information

- Name: Usermaatre Meryamun Ramesses Heqaiunu (throne name), meaning “Powerful is the Justice of Re, Beloved of Amun, Ruler of Iunu (Heliopolis).”

- Dynasty: 20th Dynasty, New Kingdom.

- Reign: Approximately 1186–1155 BCE (31 years).

- Predecessor: Tausret (after a brief period of instability).

- Successor: Ramesses IV (his son).

- Family: Son of Setnakhte (founder of the 20th Dynasty); father to multiple sons who became pharaohs, including Ramesses IV, V, VI, and VIII.

Major Achievements

- Military Campaigns: Ramesses III is best known for defending Egypt against significant external threats, particularly during the invasions of the Sea Peoples, a confederation of maritime raiders. His victories are vividly depicted in the reliefs at Medinet Habu, his mortuary temple in Thebes (modern Luxor). Key campaigns include:

- Year 5 (c. 1181 BCE): Defeated Libyan invaders, who threatened Egypt’s western borders.

- Year 8 (c. 1178 BCE): Repelled the Sea Peoples in a massive land and naval battle, often considered a turning point in preserving Egypt’s sovereignty. The reliefs at Medinet Habu show dramatic scenes of naval combat, with Egyptian archers and chariots overwhelming the invaders.

- Year 11 (c. 1175 BCE): Quelled another Libyan invasion, securing Egypt’s borders. These victories stabilized Egypt during a period when many neighboring civilizations collapsed under the Bronze Age collapse.

- Monumental Construction: Ramesses III was a prolific builder, modeling his works after his revered predecessor, Ramesses II. His most famous monument is the mortuary temple at Medinet Habu, one of the best-preserved temples of the New Kingdom. Key features include:

- Reliefs and Inscriptions: The temple’s walls depict his military triumphs, religious festivals (like the Festival of Min), and the Medinet Habu King List, honoring deified predecessors such as Ahmose I, Thutmose III, and Ramesses II.

- Fortified Complex: Medinet Habu served as a religious, administrative, and defensive hub, reflecting the turbulent times.

- Other projects: He contributed to temples at Karnak, Luxor, and built a tomb (KV11) in the Valley of the Kings, though it was left incomplete.

- Administration and Economy: Despite Egypt’s declining resources, Ramesses III maintained a robust administration. The Harris Papyrus I, a 40-meter-long document, details his donations to temples, land management, and efforts to stabilize the economy. He supported the artisans at Deir el-Medina, who built royal tombs, though labor strikes (the first recorded in history) occurred late in his reign due to delayed grain rations, signaling economic strain.

Challenges and the Harem Conspiracy

Ramesses III’s reign faced internal and external pressures:

- Economic Decline: The New Kingdom’s wealth waned due to disrupted trade routes and the cost of wars.

- Internal Unrest: The Harem Conspiracy (c. 1155 BCE), documented in the Judicial Papyrus of Turin, was a plot to assassinate Ramesses III, orchestrated by a minor queen, Tiye, to place her son, Pentawere, on the throne. The plot involved high-ranking officials and harem members. While the conspirators were tried and executed (or forced to commit suicide), it’s unclear if the assassination succeeded. Recent CT scans of Ramesses III’s mummy (discovered in the Deir el-Bahri cache, DB320) revealed a deep throat wound, suggesting he was likely killed.

The Medinet Habu Connection

Medinet Habu, located on the West Bank of Luxor, is Ramesses III’s enduring legacy. The temple complex, dedicated to Amun-Re and his deification, showcases:

- Military Reliefs: Detailed carvings of battles against the Sea Peoples and Libyans, providing historical insights into Bronze Age warfare.

- King List: The Festival of Min relief in the second courtyard lists 16 cartouches of deified kings, including 18th and 19th Dynasty rulers like Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, and Ramesses II, linking Ramesses III to Egypt’s glorious past.

- Architectural Grandeur: The temple’s fortified walls, colossal statues, and colorful reliefs reflect Ramesses III’s ambition to emulate Ramesses II’s monumental legacy.

Legacy and Death

Ramesses III’s reign stabilized Egypt during a turbulent period, but his death marked the beginning of the 20th Dynasty’s decline. His sons’ short reigns and ongoing economic challenges weakened Egypt, leading to the end of the New Kingdom. His mummy, now in Cairo’s National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, reveals a ruler who faced violent betrayal yet left an indelible mark through Medinet Habu and his military triumphs.

Cultural and Historical Significance

- Last Great Pharaoh: Ramesses III’s ability to repel invasions preserved Egypt’s sovereignty when other Bronze Age powers fell.

- Artistic Legacy: The vivid reliefs at Medinet Habu are a primary source for studying the Sea Peoples and New Kingdom art.

- Historical Insight: Documents like the Harris Papyrus and Judicial Papyrus provide rare glimpses into ancient Egyptian governance, religion, and justice.

Visiting Ramesses III’s Legacy

To explore Ramesses III’s world, visit Medinet Habu in Luxor, a UNESCO World Heritage site. Its well-preserved reliefs and serene atmosphere make it a highlight of the West Bank, often less crowded than the Valley of the Kings. Combine it with visits to Deir el-Medina or Hatshepsut’s temple for a full New Kingdom experience.

Setnakhte: Founder of the 20th Dynasty

Setnakhte (also spelled Sethnakht or Setnakht, meaning “Seth is victorious”) was the first pharaoh of Egypt’s 20th Dynasty during the New Kingdom, reigning briefly from approximately 1189–1186 BCE (about 3–4 years). He is significant for stabilizing Egypt after a period of political turmoil and founding a dynasty that included his son, Ramesses III, one of Egypt’s last great pharaohs. Setnakhte’s reign is closely tied to Medinet Habu through his son’s mortuary temple, which reflects the restored order he initiated. Below is a detailed overview of his life, achievements, and connection to Medinet Habu.

Key Information

- Name: Userkhaure-setepenre Setnakhte (throne name), meaning “Powerful are the manifestations of Re, chosen of Re.”

- Dynasty: 20th Dynasty, New Kingdom.

- Reign: c. 1189–1186 BCE (short reign, likely 3–4 years).

- Predecessor: Likely Tausret (19th Dynasty queen-pharaoh) or a period of anarchy following her rule.

- Successor: Ramesses III (his son).

- Family:

- Wife: Tiy-Merenese, a queen known from inscriptions.

- Son: Ramesses III, who succeeded him and built the iconic Medinet Habu temple.

- Possible other children, though less documented.

Historical Context and Rise to Power

Setnakhte’s ascent to the throne occurred during a chaotic period at the end of the 19th Dynasty. After the death of Merenptah (Ramesses II’s son), Egypt faced succession disputes, weak rulers (e.g., Seti II, Siptah, Amenmesse), and the brief rule of Tausret, a queen-pharaoh. The Bay, a powerful Syrian chancellor, contributed to instability by supporting rival claimants. This turmoil, combined with economic decline and external threats, created a power vacuum.

Setnakhte, whose origins are unclear, likely seized power through military or political means. He may have been a noble or military leader, possibly linked to the 19th Dynasty through marriage or service, though no definitive evidence confirms a royal lineage. The Elephantine Stele, a key source, describes Setnakhte as restoring order by expelling rebels and “Asiatic” (possibly Bay and his allies) who had disrupted Egypt. This suggests he ended a civil war or foreign influence, establishing the 20th Dynasty.

Major Achievements

- Restoration of Order:

- Setnakhte’s primary achievement was stabilizing Egypt after years of chaos. The Elephantine Stele claims he “restored the land to its proper condition,” indicating he suppressed internal revolts and reestablished central authority.

- He likely defeated forces loyal to Bay or other rivals, consolidating power and paving the way for his son’s successful reign.

- Monuments and Usurpation:

- Due to his short reign, Setnakhte left few original monuments. He is known for usurping existing structures, particularly those of his predecessors:

- He appropriated Tausret’s tomb (KV14) in the Valley of the Kings, erasing her cartouches and adding his own.

- He may have modified or claimed other 19th Dynasty monuments, a common practice to legitimize his rule.

- Inscriptions at Karnak and a stele at Elephantine (Aswan) record his efforts to restore temples and religious practices, aligning himself with traditional Egyptian kingship.

- Due to his short reign, Setnakhte left few original monuments. He is known for usurping existing structures, particularly those of his predecessors:

- Foundation of the 20th Dynasty:

- By establishing a stable succession, Setnakhte ensured his son, Ramesses III, could inherit a unified Egypt. This allowed Ramesses III to focus on defending against invasions (e.g., Sea Peoples) and building grand monuments like Medinet Habu.

Connection to Medinet Habu

While Setnakhte did not build Medinet Habu, his legacy is indirectly tied to it through his son, Ramesses III, who constructed the iconic mortuary temple in Thebes (modern Luxor). Medinet Habu’s reliefs and inscriptions reflect the stability Setnakhte restored, which enabled Ramesses III’s ambitious projects. Key connections include:

- Historical Context: The temple’s reliefs, especially those depicting Ramesses III’s victories over the Sea Peoples, build on the restored order Setnakhte achieved. Without Setnakhte’s unification, Egypt might not have withstood these invasions.

- King List: The Medinet Habu King List in the temple’s second courtyard, carved during the Festival of Min, honors deified predecessors but does not explicitly include Setnakhte. However, as Ramesses III’s father, his role in founding the dynasty is implicitly celebrated.

- Legacy: Medinet Habu’s fortified design reflects the turbulent times Setnakhte navigated, serving as both a religious and defensive complex.

Death and Burial

Setnakhte died after a brief reign, likely of natural causes, around 1186 BCE. He was buried in KV14, the tomb originally prepared for Tausret in the Valley of the Kings. His mummy has not been definitively identified, but it may have been among those found in the Deir el-Bahri cache (DB320), alongside other New Kingdom pharaohs. His son, Ramesses III, completed or modified the tomb, ensuring Setnakhte’s burial reflected his royal status.

Legacy

- Stabilizer: Setnakhte’s short reign was pivotal in ending the 19th Dynasty’s chaos, setting the stage for Ramesses III’s military and architectural achievements.

- Dynastic Founder: As the founder of the 20th Dynasty, he initiated a lineage that ruled Egypt for over a century, though the dynasty weakened after Ramesses III.

- Historical Sources: Limited records (e.g., Elephantine Stele, Harris Papyrus I via Ramesses III) make Setnakhte a somewhat enigmatic figure, but his role in restoring order is clear.

Significance and Challenges

Setnakhte’s reign bridged a critical transition in Egyptian history. His ability to unify a fractured kingdom amid economic decline and external pressures was remarkable, though his short rule limited his personal monuments. The lack of detailed records about his origins or campaigns adds mystery, but his success in establishing the 20th Dynasty underscores his importance.

Visiting Setnakhte’s Legacy

To explore Setnakhte’s impact, visit Medinet Habu in Luxor, where Ramesses III’s temple reflects the stability he inherited. The nearby Valley of the Kings, particularly KV14, offers insight into Setnakhte’s burial. Combine these with other West Bank sites like Deir el-Medina for a deeper understanding of the 20th Dynasty’s early years.

Ramesses II: The Great Pharaoh of the New Kingdom

Ramesses II, also known as Ramesses the Great or Ozymandias (Greek name), was the third pharaoh of Egypt’s 19th Dynasty during the New Kingdom, reigning from approximately 1279–1213 BCE (about 66 years). Widely regarded as one of Egypt’s most powerful and celebrated rulers, his long reign was marked by military campaigns, monumental construction, and diplomatic achievements. His legacy is intricately tied to Medinet Habu through the Medinet Habu King List, where he is honored as a deified predecessor by his successor, Ramesses III. Below is a comprehensive overview of his life, achievements, and connection to Medinet Habu.

Key Information

- Name: Usermaatre Setepenre Ramesses (throne name), meaning “The justice of Re is powerful, chosen of Re.”

- Dynasty: 19th Dynasty, New Kingdom.

- Reign: c. 1279–1213 BCE (66 years, one of the longest reigns in Egyptian history).

- Predecessor: Seti I (his father).

- Successor: Merenptah (his 13th son).

- Family:

- Parents: Seti I and Queen Tuya.

- Wives: Nefertari (principal queen, famous for her tomb and Abu Simbel temple), Isetnofret, and others (he had multiple wives).

- Children: Over 100, including Merenptah (successor), Khaemwaset (noted scholar-priest), and Bintanath (daughter-wife).

- Mummy: Found in the Deir el-Bahri cache (DB320), now in the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, Cairo.

Major Achievements

- Military Campaigns: Ramesses II is renowned for his military exploits, particularly the Battle of Kadesh (c. 1274 BCE) against the Hittites, one of the largest chariot battles in history. Key campaigns include:

- Battle of Kadesh: Fought in modern-day Syria, it resulted in a stalemate but led to the world’s first recorded peace treaty (c. 1258 BCE) with the Hittite king Hattusili III. The treaty, inscribed on clay tablets and at Karnak, stabilized Egypt’s northern borders.

- Nubian and Libyan Campaigns: He conducted campaigns to secure Egypt’s southern (Nubia) and western borders, reinforcing Egyptian dominance.

- His military feats are depicted in temples like Abu Simbel, Ramesseum, and, indirectly, Medinet Habu, where Ramesses III emulated his style.

- Monumental Construction: Ramesses II’s reign was a golden age of architecture, with numerous temples and monuments that still define Egypt’s landscape:

- Abu Simbel: Two rock-cut temples in Nubia, dedicated to Ramesses II, Nefertari, and major gods (Amun, Re, Ptah). The Great Temple’s colossal statues are iconic.

- Ramesseum: His mortuary temple in Thebes, near Medinet Habu, featuring a massive fallen statue immortalized in Shelley’s poem “Ozymandias.”

- Pi-Ramesses: His new capital in the Nile Delta, a grand city for diplomacy and military operations.

- Karnak and Luxor Temples: He expanded these with new courts, statues, and inscriptions.

- Tomb: KV7 in the Valley of the Kings, though damaged by flooding; Nefertari’s tomb (QV66) is one of the finest in the Valley of the Queens.

- Diplomacy and Legacy:

- The Kadesh Peace Treaty was a diplomatic milestone, fostering peace with the Hittites and including a marriage alliance with a Hittite princess, Maathorneferure.

- Ramesses II’s self-promotion through inscriptions and colossal statues cemented his image as a divine ruler, influencing successors like Ramesses III.

- Cultural Contributions:

- His son Khaemwaset, a high priest of Ptah, pioneered early archaeology by restoring monuments, earning the title “first Egyptologist.”

- Ramesses II’s reign saw advancements in art, with detailed reliefs and vibrant temple decorations.

Connection to Medinet Habu

While Ramesses II did not build Medinet Habu, his legacy is prominently featured in the temple constructed by Ramesses III (20th Dynasty, c. 1186–1155 BCE) on the West Bank of Luxor. Specific connections include:

- Medinet Habu King List: In the second courtyard, the Festival of Min relief lists 16 cartouches of deified kings, including Ramesses II. This veneration by Ramesses III, who modeled his reign after Ramesses II, underscores the latter’s enduring prestige. The list places Ramesses II among greats like Thutmose III and Amenhotep III, linking him to Egypt’s glorious past.

- Inspiration for Ramesses III: The Medinet Habu reliefs, especially those depicting Ramesses III’s battles against the Sea Peoples, echo Ramesses II’s Kadesh battle reliefs in style and grandeur. Ramesses III deliberately emulated Ramesses II’s monumental and propagandistic approach to legitimize his rule.

- Proximity: Medinet Habu is near the Ramesseum, Ramesses II’s mortuary temple, creating a physical and symbolic connection between the two pharaohs’ legacies on the Theban West Bank.

Challenges and Decline

Despite his successes, Ramesses II’s long reign saw challenges:

- Economic Strain: Maintaining a vast empire and monumental projects strained Egypt’s resources, setting the stage for the 19th Dynasty’s later decline.

- Succession: With over 100 children, succession disputes emerged. Merenptah, an older son, succeeded only after many brothers predeceased him.

- External Pressures: The Hittite wars and emerging threats like the Sea Peoples (faced by his successors) foreshadowed the Bronze Age collapse.

Death and Burial

Ramesses II died around 1213 BCE, likely in his early 90s, possibly from dental issues or arthritis (per his mummy’s analysis). He was buried in KV7 in the Valley of the Kings, but his mummy was later moved to the Deir el-Bahri cache (DB320) to protect it from tomb robbers. His well-preserved mummy, showing signs of red hair, reveals a tall, robust man with a prominent nose.

Legacy

- Historical Impact: Ramesses II’s reign was a high point of the New Kingdom, marked by prosperity, military prowess, and cultural achievements. His peace treaty and monuments set a standard for pharaonic power.

- Cultural Icon: Known as “Ramesses the Great,” his legacy inspired later rulers like Ramesses III and persists in modern popular culture.

- Archaeological Significance: His monuments, from Abu Simbel to the Ramesseum, are UNESCO World Heritage sites and major tourist attractions.

Visiting Ramesses II’s Legacy

To explore Ramesses II’s impact:

- Medinet Habu (Luxor): See his name in the King List and admire Ramesses III’s homage to his style.

- Ramesseum (near Medinet Habu): Visit his mortuary temple with its colossal statue remnants.

- Abu Simbel (near Aswan): Marvel at the rock-cut temples, relocated in the 1960s to save them from Lake Nasser.

- Karnak and Luxor Temples: Explore his additions to these Theban complexes.

- Valley of the Kings/Queens: Visit KV7 and Nefertari’s QV66 for a glimpse of his family’s burials.

Fun Facts

- Ramesses II’s mummy was flown to Paris in 1976 for preservation, where he received a state welcome.

- His reign’s length (66 years) is among the longest in Egyptian history, outliving many of his children.

- The Ozymandias statue at the Ramesseum inspired Percy Shelley’s poem, reflecting on the fleeting nature of power.

Merenptah: The Successor of Ramesses II

Merenptah (also spelled Merneptah or Merenptah) was the fourth pharaoh of Egypt’s 19th Dynasty during the New Kingdom, reigning from approximately 1213–1203 BCE (about 10 years). As the 13th son of Ramesses II, he ascended the throne late in life and is best known for his military campaigns, including the famous Merneptah Stele, which contains the earliest known reference to “Israel.” His legacy is tied to Medinet Habu through the Medinet Habu King List, where he is honored as a deified predecessor by Ramesses III. Below is a detailed overview of his life, achievements, and connection to Medinet Habu.

Key Information

- Name: Baenre Merynetjeru Merenptah (throne name), meaning “Soul of Re, beloved of the gods.”

- Dynasty: 19th Dynasty, New Kingdom.

- Reign: c. 1213–1203 BCE (approximately 10 years).

- Predecessor: Ramesses II (his father).

- Successor: Likely Seti II (his son) or Amenmesse (a usurper, possibly another son; succession disputed).

- Family:

- Father: Ramesses II.

- Mother: Isetnofret (one of Ramesses II’s principal wives).

- Wives: Isetnofret II (likely his sister or niece) and possibly Takhat.

- Children: Seti II (confirmed son and successor) and possibly Amenmesse (disputed).

- Mummy: Found in the Deir el-Bahri cache (DB320), now in the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, Cairo.

Historical Context

Merenptah inherited the throne after Ramesses II’s 66-year reign, a period of relative stability but growing economic and external pressures. As one of Ramesses II’s many sons, Merenptah was not initially expected to rule, outliving many of his older brothers. He likely served as a military commander and administrator under his father, gaining experience before becoming pharaoh in his late 50s or early 60s. His reign faced challenges from internal succession disputes and external threats, signaling the beginning of the 19th Dynasty’s decline.

Major Achievements

- Military Campaigns: Merenptah’s reign was marked by defensive campaigns to maintain Egypt’s control over its empire:

- Libyan Invasion (Year 5, c. 1208 BCE): Merenptah repelled a major invasion by Libyan tribes, led by the chief Meryey, allied with Sea Peoples groups like the Ekwesh and Shekelesh. The victory at Perire (in the western Delta) is detailed in the Merneptah Stele and inscriptions at Karnak, claiming over 9,000 enemies killed or captured.

- Canaanite Campaign: Merenptah conducted a campaign in Canaan to suppress rebellions in city-states like Ashkelon, Gezer, and Yanoam. The Merneptah Stele (also called the Israel Stele) from his funerary temple in Thebes records these victories and includes the earliest known mention of “Israel” as a defeated people, providing a key historical reference for biblical studies.

- Nubian Control: He maintained Egypt’s authority over Nubia, though details are sparse.

- Monuments and Building Projects: Merenptah’s short reign and advanced age limited his construction projects, but he contributed to Egypt’s monumental landscape:

- Funerary Temple: Built near the Ramesseum (Ramesses II’s mortuary temple) in Thebes, close to Medinet Habu. Much of it was constructed using stones repurposed from his father’s monuments.

- Thebes and Memphis: He added inscriptions and statues at Karnak, Luxor, and Memphis, often usurping Ramesses II’s monuments to assert his legitimacy.

- Tomb: KV8 in the Valley of the Kings, one of the largest and best-preserved tombs, decorated with scenes from the Book of the Dead and other funerary texts.

- Merneptah Stele:

- Discovered in 1896 by Flinders Petrie in Merenptah’s Theban funerary temple, this granite stele is a cornerstone of Egyptology. It celebrates his Libyan victory and lists subdued peoples in Canaan, including the famous line: “Israel is laid waste; its seed is no more.” This is the earliest extrabiblical reference to Israel, dated to c. 1208 BCE, though its exact meaning (whether referring to a people, tribe, or place) remains debated.

Connection to Medinet Habu

Merenptah is directly linked to Medinet Habu through the Medinet Habu King List, carved in the second courtyard of Ramesses III’s mortuary temple (20th Dynasty, c. 1186–1155 BCE). Key connections include:

- King List: The Festival of Min relief at Medinet Habu lists 16 cartouches of deified kings, including Merenptah, alongside his father Ramesses II, grandfather Seti I, and earlier rulers like Thutmose III and Amenhotep III. This inclusion by Ramesses III, who emulated Ramesses II, honors Merenptah’s role in maintaining the 19th Dynasty’s legacy.

- Military Influence: Merenptah’s campaigns against Libyans and Sea Peoples foreshadowed Ramesses III’s own battles, depicted in Medinet Habu’s vivid reliefs. The temple’s iconography reflects a continuity of martial propaganda from Merenptah’s era.

- Proximity: Medinet Habu is near Merenptah’s funerary temple and the Ramesseum, creating a cluster of 19th and 20th Dynasty monuments on the Theban West Bank.

Challenges and Succession

Merenptah’s reign faced significant challenges:

- Economic Decline: The New Kingdom’s wealth, strained under Ramesses II, continued to wane due to disrupted trade and costly campaigns.

- Succession Disputes: After Merenptah’s death, a power struggle emerged. Seti II, his son, was the legitimate heir, but Amenmesse, possibly another son or usurper, briefly seized control in southern Egypt, leading to a short-lived civil war.

- External Threats: The Libyan invasion and Canaanite rebellions tested Egypt’s military resources, signaling the growing pressures of the Bronze Age collapse.

Death and Burial

Merenptah died around 1203 BCE, likely in his late 60s or early 70s, possibly from natural causes (his mummy shows signs of arthritis and dental issues). He was buried in KV8 in the Valley of the Kings, a well-decorated tomb with intricate reliefs. To protect it from robbers, his mummy was later moved to the Deir el-Bahri cache (DB320), where it was discovered in 1881. Analysis of his mummy indicates he was about 5’7” tall, with signs of aging and battle-related injuries.

Legacy

- Historical Significance: Merenptah’s reign bridged the peak of the 19th Dynasty under Ramesses II and its eventual decline. His victories preserved Egypt’s empire, but internal and external pressures foreshadowed the New Kingdom’s end.

- Merneptah Stele: The reference to “Israel” makes Merenptah a key figure in both Egyptology and biblical archaeology, sparking debates about early Israelite history.

- Cultural Impact: His inclusion in the Medinet Habu King List reflects his enduring prestige, despite a relatively modest reign compared to his father.

Visiting Merenptah’s Legacy

To explore Merenptah’s contributions:

- Medinet Habu (Luxor): See his name in the Medinet Habu King List and connect his legacy to Ramesses III’s temple.

- Valley of the Kings: Visit KV8, his well-preserved tomb, showcasing New Kingdom funerary art.

- Karnak Temple: View his inscriptions and victory reliefs, including those related to the Libyan campaign.

- National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (Cairo): Examine his mummy for insights into his physical condition.

Fun Facts

- The Merneptah Stele’s mention of “Israel” is the only known Egyptian reference to this entity, making it a critical artifact for historians.

- Merenptah’s advanced age at ascension (likely 60s) was unusual, as many of his brothers predeceased their long-lived father, Ramesses II.

- His tomb (KV8) features one of the earliest uses of the Amduat, a key funerary text, on its walls.

Seti II: A Pharaoh Amid Dynastic Turmoil

Seti II was the fifth pharaoh of Egypt’s 19th Dynasty during the New Kingdom, reigning from approximately 1203–1197 BCE (about 6 years). As the son of Merenptah and grandson of Ramesses II, he ruled during a period of declining Egyptian power marked by internal strife and a rival claimant, Amenmesse. His legacy is connected to Medinet Habu through the Medinet Habu King List, where he is honored as a deified predecessor by Ramesses III. Below is a detailed overview of his life, achievements, and ties to Medinet Habu.

Key Information

- Name: Userkheperure Setepenre Seti (throne name), meaning “Powerful are the manifestations of Re, chosen of Re.”

- Dynasty: 19th Dynasty, New Kingdom.

- Reign: c. 1203–1197 BCE (approximately 6 years).

- Predecessor: Merenptah (his father).

- Successor: Siptah (likely his son) or Tausret (his widow, who ruled as queen-pharaoh).

- Family:

- Father: Merenptah.

- Mother: Isetnofret II (likely Merenptah’s principal wife).

- Wives: Tausret (principal queen, later pharaoh), Takhat, and possibly others.

- Children: Siptah (likely his son, though possibly Amenmesse’s; disputed).

- Mummy: Likely found in the Deir el-Bahri cache (DB320), though identification is uncertain; possibly among mummies in the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, Cairo.

Historical Context

Seti II ascended the throne after the death of his father, Merenptah, during a time of economic strain and political instability in the late 19th Dynasty. The long reign of Ramesses II and Merenptah’s rule had stretched Egypt’s resources, and external threats like the Sea Peoples and Libyan invasions loomed. Seti II’s reign was disrupted by a usurper, Amenmesse, who may have been a rival prince or another son of Merenptah, leading to a brief civil war or regional division. Despite these challenges, Seti II maintained control in northern Egypt and left a modest legacy.

Major Achievements

- Restoration of Authority:

- Seti II faced a challenge from Amenmesse, who seized control of southern Egypt (Thebes and Nubia) for a few years, possibly during Seti II’s early reign. Seti II likely reasserted control by Year 3 or 4, as evidenced by his inscriptions overwriting Amenmesse’s in Thebes.

- His ability to reclaim Upper Egypt demonstrates resilience, though the brevity of his reign limited further consolidation.

- Monuments and Building Projects:

- Due to his short reign and the rivalry with Amenmesse, Seti II’s construction projects were modest compared to his predecessors:

- Karnak Temple: He added a small triple shrine (bark station) for the Theban triad (Amun, Mut, Khonsu) in the Karnak complex, still visible today.

- Thebes: He left inscriptions and reliefs in Thebes, often usurping or erasing Amenmesse’s monuments to assert legitimacy.

- Tomb: KV15 in the Valley of the Kings, a simple but well-decorated tomb with reliefs from the Litany of Re and other funerary texts. It was left incomplete, likely due to his early death.

- Tausret’s Tomb: He initiated KV14 for his queen, Tausret, which she later expanded as pharaoh and was usurped by Setnakhte.

- Due to his short reign and the rivalry with Amenmesse, Seti II’s construction projects were modest compared to his predecessors:

- Administration:

- Seti II maintained Egypt’s administrative structure, with key officials like the chancellor Bay (a Syrian who later supported Siptah and Tausret) playing a prominent role. Bay’s influence, however, contributed to later instability.

- He continued oversight of Deir el-Medina, the artisans’ village near Medinet Habu, ensuring the continuation of tomb-building projects.

Connection to Medinet Habu

Seti II is linked to Medinet Habu through the Medinet Habu King List, located in the second courtyard of Ramesses III’s mortuary temple (20th Dynasty, c. 1186–1155 BCE) on the West Bank of Luxor. Key connections include:

- Medinet Habu King List: The Festival of Min relief lists 16 cartouches of deified kings, including Seti II, alongside his father Merenptah, grandfather Ramesses II, and great-grandfather Seti I. This inclusion by Ramesses III, who sought to emulate the 19th Dynasty’s grandeur, underscores Seti II’s place in the royal lineage despite his troubled reign.

- Historical Continuity: The Medinet Habu reliefs, particularly those depicting Ramesses III’s victories, reflect the martial tradition of the 19th Dynasty, which Seti II upheld during his conflicts with Amenmesse.

- Proximity: Medinet Habu is near Seti II’s tomb (KV15) and Merenptah’s funerary temple, connecting the 19th and 20th Dynasties’ monumental legacy on the Theban West Bank.

Challenges and Succession

Seti II’s reign was marked by significant challenges:

- Rivalry with Amenmesse: Amenmesse’s usurpation in Upper Egypt (Thebes and Nubia) split the kingdom, with Seti II controlling Lower Egypt (Memphis and the Delta). The conflict’s resolution is unclear, but Seti II’s erasure of Amenmesse’s monuments suggests he regained full control.

- Economic Decline: The New Kingdom’s wealth continued to dwindle, strained by previous wars and monumental projects, limiting Seti II’s resources.

- Succession Crisis: After Seti II’s death, his young son Siptah (or possibly Amenmesse’s son) became pharaoh under the regency of Tausret and chancellor Bay. This led to further instability, culminating in Tausret’s brief rule as pharaoh and the rise of Setnakhte, who founded the 20th Dynasty.

Death and Burial

Seti II died around 1197 BCE, likely in his 40s, possibly from illness (no definitive evidence from his mummy exists). He was buried in KV15 in the Valley of the Kings, a modestly decorated tomb left unfinished. His mummy was likely moved to the Deir el-Bahri cache (DB320) to protect it from tomb robbers, but its identification remains uncertain due to poor preservation and incomplete records. Some Egyptologists propose a mummy labeled “Unknown Man E” could be Seti II, though this is speculative.

Legacy

- Historical Significance: Seti II’s reign was a brief but critical link in the 19th Dynasty, maintaining Egypt’s stability despite internal division. His victory over Amenmesse preserved the legitimate royal line.

- Cultural Impact: His inclusion in the Medinet Habu King List reflects his recognized status, though his reign was overshadowed by his predecessors’ grandeur and successors’ turmoil.

- Archaeological Record: His monuments, though limited, and his tomb (KV15) provide insights into the 19th Dynasty’s final years.

Visiting Seti II’s Legacy

To explore Seti II’s contributions:

- Medinet Habu (Luxor): See his name in the Medinet Habu King List and connect his legacy to Ramesses III’s temple.

- Valley of the Kings: Visit KV15, his tomb, and KV14, started for Tausret and later usurped by Setnakhte.

- Karnak Temple: View his triple shrine for the Theban triad, a rare surviving monument from his reign.

- National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (Cairo): Examine mummies from the Deir el-Bahri cache, potentially including Seti II’s.

Fun Facts

- Seti II’s rivalry with Amenmesse is one of the few documented instances of a divided Egypt during the New Kingdom, highlighting the dynasty’s fragility.

- His queen, Tausret, became one of Egypt’s few female pharaohs, ruling after Siptah’s death.

- The chancellor Bay, a controversial figure, inscribed his name in Seti II’s tomb, an unusual act for a non-royal.

Visiting Medinet Habu

For travelers, Medinet Habu offers an intimate alternative to Luxor’s busier attractions. Its well-preserved reliefs, including dramatic scenes of Ramesses III’s battles against the Sea Peoples, provide unparalleled insights into ancient Egyptian military and religious life. The site’s relative tranquility allows for unhurried exploration, perfect for photography or soaking in the ambiance of a 3,000-year-old monument.

Located near Deir el-Medina, the workers’ village, Medinet Habu also sheds light on the lives of the artisans who crafted Egypt’s iconic tombs. Guided tours from Luxor often combine these sites, making it easy to explore the West Bank’s rich heritage in a day.

Tips for Visiting Medinet Habu

Best Time to Visit: Early morning to avoid the heat and enjoy softer light for photography.

What to Bring: Comfortable shoes, water, and a hat for sun protection.

How to Get There: Easily accessible by taxi or tour from Luxor; consider pairing with visits to the Valley of the Kings or Hatshepsut’s temple.

Highlights to Look For: The Sea Peoples reliefs, the Festival of Min king list, and the colorful hypostyle halls.

A Timeless Journey

Medinet Habu is more than a temple; it’s a portal to the grandeur of ancient Egypt. From Ramesses III’s military victories to the sacred king list honoring his predecessors, the site encapsulates the power, artistry, and spirituality of the New Kingdom. Whether you’re drawn to its historical significance or its architectural splendor, Medinet Habu promises an unforgettable journey into Egypt’s past.

Plan your visit to Medinet Habu today and discover why this hidden gem deserves a place on every traveler’s itinerary!

.

Easy & Secure Booking

Visiting Medinet Habu 2026 now through:

🌐 Official Website: hurghadatogo.com

📧 Email: [email protected]

📱 WhatsApp: +201009255585

We also recommend you :

St Paul & St Anthony Monasteries Day Tour from Hurghada/Cairo 2026