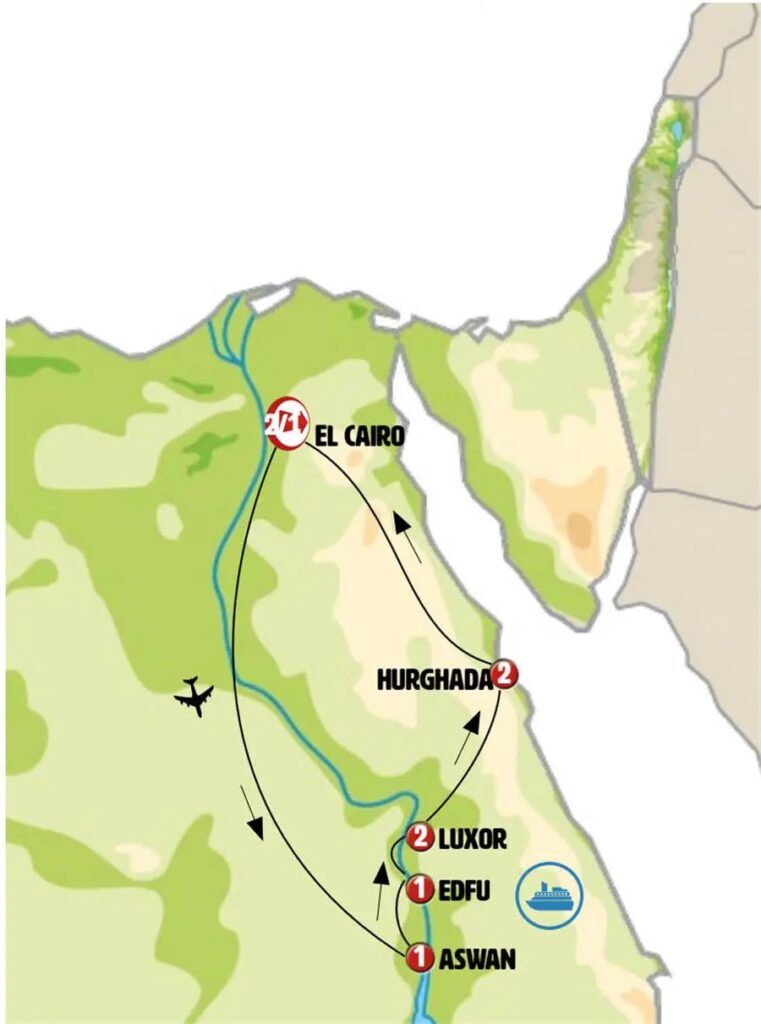

Al-Ghardaqah (Hurghada), Egypt

Al-Ghardaqah (commonly known internationally as Hurghada) is a major tourist city located on the Red Sea coast of Egypt. It is one of the most popular destinations in the country, especially for visitors who enjoy the sea, sun, and desert adventures.

Key Facts

Location: Eastern Egypt, along the Red Sea, about 450 km southeast of Cairo.

Population: Around 300,000 residents.

Climate: Subtropical desert climate, sunny all year round with very mild winters and hot summers.

Airport: Hurghada International Airport (HRG), with flights connecting to many European, Middle Eastern, and domestic cities.

Tourism Highlights

Marine Life & Diving: Famous for coral reefs, shipwrecks, and rich marine biodiversity. Ideal for scuba diving, snorkeling, and glass-bottom boat trips.

Beaches: Long stretches of sandy beaches and turquoise waters.

Islands: Giftun Island, Mahmya, Orange Bay, and Eden Island are among the top excursion spots.

Day Trips: Popular trips include Luxor, Cairo, the Pyramids, and desert safaris.

Water Sports: Kite surfing, windsurfing, parasailing, and yachting are widely available.

History

Originally a small fishing village, Hurghada (Al-Ghardaqah) grew rapidly in the late 20th century into a leading international resort, attracting millions of tourists every year.

Al-Ghardaqah (Hurghada) is the capital of the Al-Baḥr al-Aḥmar Governorate in Egypt. Once a modest Red Sea port, the town has developed into a center of industry and tourism. Its economy is strongly linked to oil exploration and production, with a major oil field located nearby, making it an important administrative and logistical hub for the oil operations in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Suez.

In addition to its industrial role, Al-Ghardaqah is home to a marine biology research station, which focuses on oceanography and fisheries studies. The city is also well connected by a coastal highway that runs north to Suez (Al-Suways) and south to Al-Quṣayr, facilitating both trade and travel.

As of the 2006 census, the population was recorded at 160,901 residents, though the number has grown significantly in recent years due to the expansion of tourism and infrastructure.

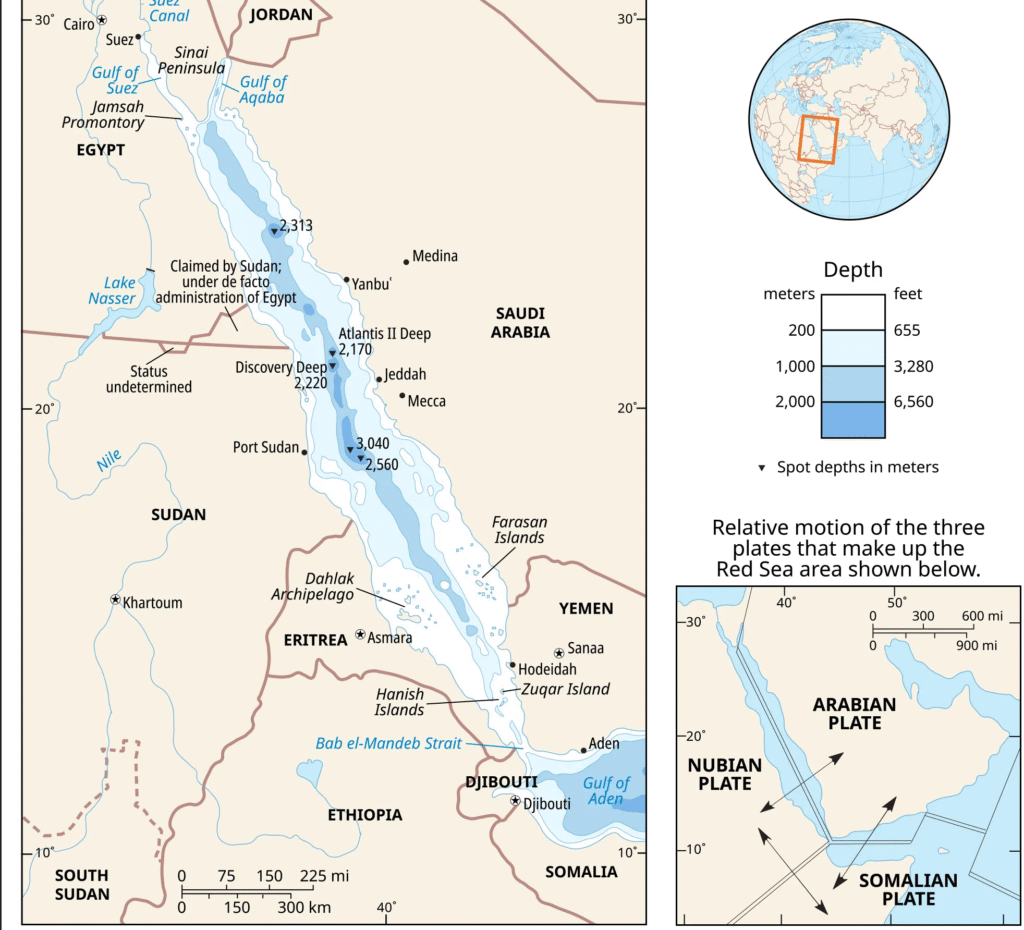

Red Sea — Middle East

The Red Sea is a long, narrow body of water stretching southeast for about 1,200 miles (1,930 km) from Suez, Egypt, to the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, which links it to the Gulf of Aden and ultimately the Arabian Sea. From a geological perspective, the Gulfs of Suez and Aqaba (Elat) are regarded as the northern extensions of the same rift system.

The sea forms a natural boundary, separating the coastlines of Egypt, Sudan, and Eritrea on the west from those of Saudi Arabia and Yemen on the east. At its widest point, the Red Sea spans about 190 miles (305 km), while its greatest depth reaches 9,974 feet (3,040 metres). Covering an area of roughly 174,000 square miles (450,000 square km), it is one of the world’s most distinctive and strategically important waterways.

The Red Sea is known for having some of the warmest and saltiest seawater in the world. Linked to the Mediterranean Sea through the Suez Canal, it serves as one of the busiest maritime routes on the globe, facilitating trade between Europe and Asia.

The sea’s name is believed to come from the color variations in its waters. While it usually appears a striking blue-green, at times it experiences large blooms of the algae Trichodesmium erythraeum. When these algae die off, they can turn the surface waters a reddish-brown hue, giving rise to the name “Red Sea.”

This discussion focuses specifically on the Red Sea and its northern extensions—the Gulfs of Suez and Aqaba. For more detailed information on the Suez Canal, see the separate entry on that subject.

Physical Features

Physiography and Submarine Morphology

The Red Sea occupies a fault depression that divides two major crustal blocks—the Arabian Peninsula to the east and North Africa to the west. This rift valley structure shapes both the sea and its surrounding landscapes.

Inland from the coastal plains, the terrain rises sharply, with elevations exceeding 6,560 feet (2,000 metres) above sea level. The southern regions are particularly elevated, marking the highest points along the Red Sea’s borders.

(Maps of the region often highlight both the physiography of the Red Sea and the relative movement of the tectonic plates that define it.)

At its northern end, the Red Sea divides into two extensions: the Gulf of Suez to the northwest and the Gulf of Aqaba to the northeast. The Gulf of Suez is relatively shallow, with depths ranging from 180 to 210 feet (55–65 metres), and is bordered by a wide coastal plain. In contrast, the Gulf of Aqaba is much deeper, plunging to about 5,500 feet (1,675 metres), and is edged by a narrow plain.

From approximately 28° N latitude, where the two gulfs meet, down to about 25° N latitude, the coasts of the Red Sea run nearly parallel, separated by a distance of around 100 miles (160 km). Within this stretch, the seafloor forms a central trough that mirrors the coastlines, reaching depths of up to 4,000 feet (1,220 metres).

South of this point, extending southeast to about 16° N latitude, the main trough of the Red Sea takes on a sinuous course, reflecting the irregular shape of the shoreline. Around 20° to 21° N latitude, the seafloor becomes increasingly rugged, marked by a series of sharp clefts and fractures.

Further south, extensive coral growth transforms much of the seabed, leaving only a shallow, narrow channel beyond 16° N. At the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, where the Red Sea meets the Gulf of Aden, a submarine ridge (sill) rises. Coral development on this ridge reduces the depth of the passage to just about 380 feet (116 metres), narrowing the main channel significantly.

Within the deeper sections of the Red Sea trough lie remarkable clefts on the seafloor, where hot brine pools are concentrated. These isolated pockets create distinct sub-basins, aligned in a north–south direction, contrasting with the overall northwest–southeast orientation of the main trough.

At the bottoms of these brine-filled depressions are layers of unusual sediments, consisting of heavy metal oxide deposits that can reach 30 to 60 feet (9–18 metres) in thickness.

Most of the islands in the Red Sea are little more than emergent coral reefs. However, there are notable exceptions: a chain of active volcanoes lies just south of the Dahlak Archipelago (15°50′ N), and the island of Jabal al-Ṭāʾir hosts a recently extinct volcano.

Geology

The Red Sea lies within a major rift valley that divides the continental crust of Africa from that of Arabia. This rift is part of a vast and complex tectonic system. To the south, it connects with the East African Rift System, which stretches through Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania for nearly 2,200 miles (3,540 km). To the north, it extends more than 280 miles (450 km) beyond the Gulf of Aqaba, forming the great Wadi Aqaba–Dead Sea–Jordan Rift. From the southern end of the Red Sea, the system also continues eastward for some 600 miles (965 km), creating the Gulf of Aden.

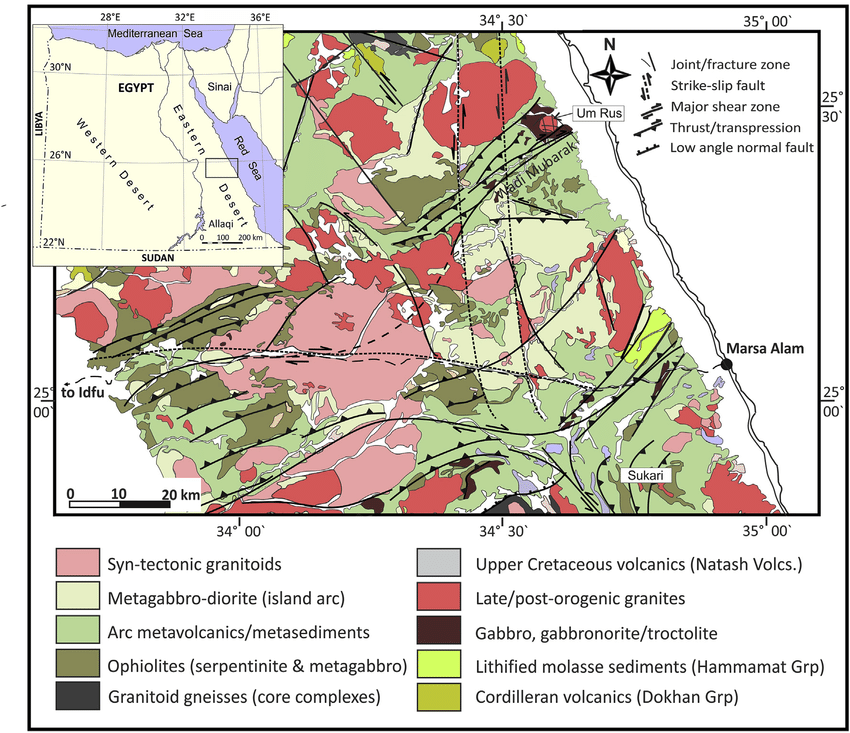

The Red Sea valley cuts through the Arabian-Nubian Massif, a once-continuous block of Precambrian igneous and metamorphic rocks formed more than 540 million years ago under intense heat and pressure. These rocks are exposed today as the rugged mountain ranges flanking the sea. Surrounding the massif are layers of Paleozoic marine sediments (542–251 million years old), which were later folded and faulted during tectonic activity. Deposition continued through this period and extended into the Mesozoic Era (251–65.5 million years ago).

Mesozoic sediments largely encircle and overlap the Paleozoic layers and are themselves overlain by deposits from the early Cenozoic Era (65.5–55.8 million years ago). In many areas, remnants of these Mesozoic deposits still rest atop the Precambrian rocks, indicating that a once continuous sedimentary cover stretched across the ancient massif.

The Red Sea is considered a geologically young sea, with a developmental history thought to resemble the early formation of the Atlantic Ocean. Its trough emerged through at least two major phases of tectonic activity.

The first phase began when Africa started drifting away from Arabia roughly 55 million years ago. During this period, the Gulf of Suez opened around 30 million years ago, followed by the northern Red Sea about 20 million years ago.

The second phase occurred between 3 and 4 million years ago, shaping the trough of the Gulf of Aqaba as well as the southern section of the Red Sea valley. Tectonic movement continues today at an estimated rate of 0.59 to 0.62 inch (15–15.7 mm) per year, as evidenced by frequent volcanic activity in the past 10,000 years, ongoing seismic events, and the presence of hot brine flows along the trough.

Climate

The Red Sea region is characterized by an arid climate, with very little precipitation throughout the year. Archaeological evidence, however, suggests that in prehistoric times the area experienced periods of significantly higher rainfall.

For much of the year—particularly in autumn, winter, and spring—the climate is generally favorable for outdoor activities, except during the occasional windstorms. Temperatures during these seasons typically range between 46 and 82 °F (8–28 °C). In summer, conditions become more extreme, with temperatures soaring up to 104 °F (40 °C). Combined with high humidity, this makes strenuous physical activity uncomfortable.

Wind patterns vary across the region. In the northern Red Sea, down to about 19° N, prevailing winds blow from the north to northwest. Among these are the well-known seasonal westerly “Egyptian” winds, which occur in winter and often bring fog and sandstorms. Between 14° and 16° N latitude, winds are more variable, but from June through August, strong northwest winds dominate, occasionally reaching as far south as the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. By September, this wind system retreats northward beyond 16° N. South of 14° N, prevailing winds shift, generally blowing from the south and southeast.

Hydrology

The Red Sea receives no river inflow and only minimal rainfall. However, its high evaporation rate—exceeding 80 inches (200 cm) annually—is balanced by the inflow of water from the Gulf of Aden through the eastern channel of the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. Driven northward by prevailing winds, this incoming water has relatively low salinity (around 36 parts per thousand) and forms the surface circulation of the sea.

In contrast, water from the Gulf of Suez is much saltier—about 40 parts per thousand—due to intense evaporation, which increases its density. This dense water flows southward beneath the lighter, less saline waters entering from the Bab el-Mandeb.

Between 300 and 1,300 feet (90–400 metres) lies a transition zone. Below this depth, water conditions remain remarkably stable, with temperatures near 72 °F (22 °C) and salinity close to 41 parts per thousand. This dense bottom water, displaced from the north, eventually spills over the sill at Bab el-Mandeb, again through the eastern channel.

It is estimated that the entire volume of the Red Sea is renewed approximately every 20 years, maintaining its unique hydrological balance.

Beneath the southward-flowing waters of the Red Sea, in its deepest troughs, lies a thin transition layer only about 80 feet thick. Below this, at depths of roughly 6,400 feet, exist pools of hot brine. In the Atlantis II Deep, this brine reaches an average temperature of nearly 140 °F (60 °C), with an extreme salinity of 257 parts per thousand and a complete absence of oxygen. Similar brine pools are also found in the Discovery Deep and the Chain Deep (near 21°18′ N). Because these pools are heated from beneath, they remain unstable, continually mixing with the overlying waters and ultimately merging into the Red Sea’s broader circulation system.

Economic Aspects

Resources

The Red Sea region is rich in natural resources, with five major types of mineral deposits:

Petroleum and natural gas

Evaporite deposits (formed through evaporation, including halite, sylvite, gypsum, and dolomite)

Sulfur

Phosphates

Heavy-metal deposits found in the seabed oozes of the Atlantis II, Discovery, and other deep basins

Oil and gas reserves have been tapped to varying extents by the countries bordering the Red Sea. Significant deposits occur near the Jamsah (Gemsa) Promontory in Egypt, at the junction of the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea.

Although evaporites are abundant, their exploitation has so far remained limited and mostly local. Sulfur, by contrast, has been mined extensively since the early 20th century, especially from the Jamsah Promontory deposits. Phosphate reserves also exist on both sides of the sea, but their relatively low ore quality has so far made large-scale commercial extraction unprofitable with current technologies.

None of the heavy metal deposits of the Red Sea have yet been commercially exploited, although studies suggest they hold considerable potential value. In particular, the Atlantis II Deep is estimated to contain sediments of significant economic importance. Analyses of samples from its upper 30 feet reveal an average composition of 29% iron, 3.4% zinc, 1.3% copper, along with trace amounts of lead, silver, and gold. The total brine-free sediment in this upper layer is thought to amount to roughly 50 million tons.

These deposits likely extend down to about 60 feet below the current sediment surface, though the quality beyond 30 feet remains uncertain. Other locations, such as the Discovery Deep and several additional sites, also contain metalliferous sediments, but at lower concentrations than those of the Atlantis II Deep, reducing their economic appeal.

One of the greatest challenges lies in the recovery process, as these sediments are located beneath 5,700 to 6,400 feet of water. However, because much of the material exists as fluid oozes, it may be feasible to extract them by pumping—similar to methods used in oil production. Various proposals have also been made to dry and process (beneficiate) these deposits for smelting and further industrial use.

Navigation

The Red Sea plays a vital role in global maritime trade, particularly as the main passageway to the Suez Canal, which dramatically shortens shipping routes between Asia and Europe. By passing through the canal via the Red Sea, ships avoid the long detour around the Cape of Good Hope at Africa’s southern tip, saving thousands of miles and several days of travel.

Despite its importance, navigation in the Red Sea is challenging. In the northern half, the coastline is relatively straight and offers few natural harbors. In the southern half, extensive coral reef formations restrict navigable channels and even block access to some harbors. At the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, the critical gateway between the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, constant blasting and dredging are required to keep the channel open for shipping.

Further hazards include heat shimmer, which distorts visibility, sandstorms that reduce navigation accuracy, and irregular water currents, all of which make safe passage demanding for even experienced mariners.

Study and Exploration

The Red Sea is among the earliest large bodies of water recorded in human history. As early as 2000 BCE, it played a central role in Egyptian maritime trade, serving as a route for expeditions and commerce. By around 1000 BCE, it was being used as a waterway to India, and by 1500 BCE it is believed to have been well-charted, since Queen Hatshepsut of Egypt successfully dispatched an expedition that sailed its full length.

Later, around 600 BCE, the Phoenicians explored its coasts during their legendary circumnavigation of Africa. Attempts to connect the Nile River to the Red Sea through shallow canals were made before the 1st century CE, but these early projects were later abandoned. A proposal for a more ambitious connection between the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea was first made around 800 CE by the Abbasid caliph Hārūn al-Rashīd, yet it was not until 1869 that the vision became reality with the completion of the Suez Canal, a project overseen by French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps.

In the modern era, the Red Sea has been a major focus of scientific study, particularly since World War II. Landmark research expeditions included the Swedish vessel Albatross in 1948 and the American Glomar Challenger in 1972. These missions investigated the Red Sea’s chemical, biological, and geological properties, with much of the geological research closely tied to oil exploration.

Economic Aspects

Resources

The Red Sea region is rich in natural resources, with five principal categories identified: petroleum deposits, evaporite minerals (such as halite, sylvite, gypsum, and dolomite), sulfur, phosphates, and heavy-metal deposits concentrated in the deep-sea oozes of sites such as the Atlantis II Deep and Discovery Deep.

Oil and natural gas reserves have been extensively exploited by nations bordering the Red Sea, particularly around the Jamsah (Gemsa) Promontory in Egypt, where the Gulf of Suez meets the Red Sea. By contrast, evaporite deposits—despite being abundant—have been only modestly developed and used primarily on a local scale. Sulfur mining has been significant since the early 20th century, especially in the Jamsah area, while phosphate deposits are present on both shores of the Red Sea but remain largely unexploited due to their low ore quality under current extraction technologies.

The heavy-metal deposits of the Red Sea floor remain untapped, though surveys indicate enormous potential. For example, sediments in the Atlantis II Deep are estimated to contain around 50 million tons of brine-free material within the upper 30 feet, with an average composition of 29% iron, 3.4% zinc, 1.3% copper, and traces of lead, silver, and gold. These deposits likely extend to about 60 feet below the seabed, though their quality beyond 30 feet is uncertain. Other deeps, such as the Discovery Deep, also hold metalliferous sediments, albeit in lower concentrations.

Extraction poses significant challenges, as these deposits lie beneath 5,700 to 6,400 feet of water. However, their fluid, ooze-like consistency suggests that recovery by pumping methods similar to oil extraction may be feasible. Numerous proposals have been made for drying and processing these sediments to make them suitable for smelting and industrial use.

Navigation

The Red Sea is a crucial artery of global maritime trade, especially as the southern approach to the Suez Canal. The canal provides ships with a dramatically shorter route between Asia and Europe, eliminating the need to sail around the Cape of Good Hope at Africa’s southern tip, thereby saving thousands of miles and several days of travel.

Despite its importance, navigation within the Red Sea is challenging. In its northern section, the straight, unindented coastlines provide few natural harbors, while in the southern section, extensive coral reef growth narrows channels and obstructs harbor access. At the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, the vital gateway linking the Red Sea with the Gulf of Aden, constant dredging and blasting are required to keep shipping lanes open. Additional hazards include heat shimmer, sandstorms, and irregular water currents, all of which make navigation complex and demanding.

Study and Exploration

The Red Sea has held historical significance since antiquity, being one of the earliest major seas mentioned in recorded history. As early as 2000 BCE, it was integral to Egyptian maritime trade, and by 1000 BCE, it served as a recognized water route to India. By 1500 BCE, the sea was likely well-charted, as demonstrated by the famous expedition of Queen Hatshepsut, who dispatched ships to sail its full length.

Around 600 BCE, the Phoenicians explored its coasts during their circumnavigation of Africa. Early attempts to link the Nile River to the Red Sea through shallow canals occurred before the 1st century CE, but these projects were later abandoned. A more ambitious vision to connect the Mediterranean Sea with the Red Sea was proposed around 800 CE by the Abbasid caliph Hārūn al-Rashīd. However, it was not until 1869 that this dream was realized with the construction of the Suez Canal, overseen by French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps.

In modern times, the Red Sea has become an important subject of scientific research, particularly after World War II. Notable expeditions include the Swedish research vessel Albatross in 1948 and the American Glomar Challenger in 1972. These studies not only advanced knowledge of the Red Sea’s biological and chemical systems but also contributed significantly to understanding its geological structure, much of it linked to oil exploration.

Land of Egypt

Egypt shares land borders with Libya to the west, Sudan to the south, and Israel to the northeast. Its frontier with Sudan includes two disputed areas: the Ḥalāʾib Triangle along the Red Sea coast and Biʾr Ṭawīl further inland, both subject to competing territorial claims (see Researcher’s Note). To the north, Egypt’s Mediterranean coastline stretches about 620 miles (1,000 km), while to the east, its Red Sea and Gulf of Aqaba coasts extend roughly 1,200 miles (1,900 km).

Relief

Physical Features of Egypt

The landscape of Egypt is largely shaped by the Nile River. Over a stretch of approximately 750 miles (1,200 km) as it flows northward through the country, the river carves a narrow, fertile valley through the surrounding desert, creating a striking contrast between the lush greenery of the valley and the arid desolation around it. From Lake Nasser in the south to Cairo in the north, the Nile is confined within a trench-like valley bordered by cliffs. Near Cairo, these cliffs fade, and the river spreads out into its expansive delta. Together, the Nile and its delta constitute the first of Egypt’s four major physiographic regions, alongside the Western Desert (Al-Ṣaḥrāʾ al-Gharbiyyah), the Eastern Desert (Al-Ṣaḥrāʾ al-Sharqiyyah), and the Sinai Peninsula.

The Nile effectively divides the desert plateau into two uneven regions: the Western Desert, stretching toward the Libyan border, and the Eastern Desert, extending to the Suez Canal, the Gulf of Suez, and the Red Sea. Each of these deserts possesses unique characteristics. The Western Desert, part of the larger Libyan Desert, is arid and largely devoid of wadis (dry riverbeds), while the Eastern Desert is dissected by numerous wadis and lined with rugged mountains along the east. Central Sinai features open desert terrain interspersed with isolated hills and carved by seasonal riverbeds.

Contrary to common belief, Egypt is not entirely flat. In addition to the mountain ranges along the Red Sea, notable highlands exist in the far southwest of the Western Desert and in southern Sinai. The southwestern elevations are part of the ʿUwaynāt mountain range, which extends just beyond Egyptian borders.

Egypt’s coastal regions, apart from the Nile Delta, are generally hemmed in by either desert or mountains, making them arid or only marginally fertile. The northern and eastern coastal plains are narrow, rarely exceeding 30 miles (48 km) in width. Except for major cities such as Alexandria, Port Said, and Suez, as well as smaller ports and resorts like Marsā Maṭrūh and Al-ʿAlamayn (El-Alamein), these coastal areas are sparsely populated and remain underdeveloped.

The Nile Valley and Delta

The Nile Delta, also known as Lower Egypt, spans approximately 9,650 square miles (25,000 sq km). It stretches about 100 miles (160 km) from Cairo to the Mediterranean, with a coastline of roughly 150 miles (240 km) extending from Alexandria to Port Said. Historically, the delta had as many as seven branches, but today its waters flow mainly through two channels: the Damietta Branch in the east and the Rosetta Branch in the west. While the delta is largely flat, interrupted only by occasional mounds rising through the alluvial soil, it is far from featureless. A network of canals and drainage channels crisscrosses the region, and much of the coastal area is occupied by brackish lagoons such as lakes Maryūṭ, Idkū, Burullus, and Manzilah. The introduction of perennial irrigation has enabled farmers to cultivate two or three crops annually over more than half of the delta’s area.

The cultivated Nile valley between Cairo and Aswān varies in width from 5 to 10 miles (8–16 km), occasionally narrowing to a few hundred yards or widening to 14 miles (23 km). Since the completion of the Aswan High Dam in 1970, the 3,900-square-mile (10,100 sq km) valley has been continuously irrigated. Before the creation of Lake Nasser behind the dam, the Nubian Nile Valley extended 160 miles (250 km) between Aswān and the Sudanese border—a narrow, scenic gorge with limited farmland. Around 100,000 residents were relocated, primarily to government-built villages in New Nubia at Kawm Umbū (Kom Ombo) north of Aswān. Lake Nasser, developed in the 1970s, has since become a hub for fishing and tourism, with settlements emerging along its shores.

The Eastern Desert

The Eastern Desert occupies nearly one-fourth of Egypt’s land area, covering about 85,690 square miles (221,900 sq km). Its northern section forms a limestone plateau of rolling hills, stretching from the Mediterranean coastal plain to a point near Qinā on the Nile. Near Qinā, cliffs rise to about 1,600 feet (500 m), deeply cut by wadis that make the terrain challenging to traverse. Some wadi outlets form deep bays that host small semi-nomadic communities.

South of Qinā, the sandstone plateau extends toward the Red Sea, deeply indented by ravines, some of which serve as natural routes. The southernmost section comprises the Red Sea Hills and the narrow coastal plain, running from near Suez to the Sudanese border. These hills, although not a continuous range, include several interlocking systems, with peaks exceeding 6,000 feet (1,800 m). The highest, Mount Shāʿib al-Banāt, reaches 7,175 feet (2,187 m). The Red Sea Hills are geologically complex, consisting of ancient igneous and metamorphic rocks, including granite near Aswān that extends across the Nile to form the First Cataract. The narrow coastal plain widens southward, and nearly continuous coral reefs parallel the shoreline, giving the Red Sea littoral its distinct character.

The Western Desert

The Western Desert makes up about two-thirds of Egypt’s land area, covering roughly 262,800 square miles (680,650 sq km). Its highest point is on the Al-Jilf al-Kabīr plateau in the southeast, rising above 3,300 feet (1,000 m). From there, the desert slopes northeast toward depressions that characterize the region, including the oases of Al-Khārijah and Al-Dākhilah. Further north lie the Al-Farāfirah and Al-Baḥriyyah oases, while the Qattara Depression to the northwest is largely uninhabited and impassable by modern vehicles. The Siwa Oasis, west of the Qattara Depression near the Libyan border, is the largest and most historically inhabited. South of the Qattara Depression, the Western Desert is a mix of sand ridges and stony plains. Along the Mediterranean coast, the plateau edge leaves a narrow, sparsely populated coastal strip.

Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula is a triangular landmass with its base along the Mediterranean and its apex at the Gulfs of Suez and Aqaba, covering roughly 23,000 square miles (59,600 sq km). Its southern region is dominated by rugged mountains, with peaks exceeding 8,000 feet (2,400 m), including Egypt’s highest, Mount Catherine (Jabal Kātrīnā) at 8,668 feet (2,642 m). The central plateau consists of Al-Tīh and Al-ʿAjmah, both deeply cut by valleys and sloping northward toward Wadi al-ʿArīsh. The northern plateau features dome-shaped hills and sand dunes exceeding 300 feet (100 m). Along the coast lies Lake Bardawīl, a salt lagoon stretching approximately 60 miles (95 km).

Drainage

Apart from the Nile, Egypt’s natural perennial rivers are limited to a few streams in the southern Sinai mountains. Most valleys in the Eastern Desert drain westward toward the Nile and remain dry except during heavy rainstorms, particularly in the Red Sea Hills. Shorter valleys on the eastern Red Sea flank drain toward the sea, also remaining normally dry. In Sinai, mountain drainage flows toward the gulfs of Suez and Aqaba, forming deeply eroded, dry valleys. The central Sinai plateau drains northward into Wadi al-ʿArīsh, which occasionally carries surface water. In the Western Desert, surface drainage is almost absent due to aridity, though an extensive underground water table provides wells for some oases.

Soils of Egypt

Outside the Nile’s silt-rich areas, the availability and quality of cultivable soil in Egypt largely depend on local water sources and the underlying rock type. Nearly one-third of Egypt’s land is covered by Nubian sandstone, which extends across the southern portions of both the Eastern and Western deserts. Limestone deposits of Eocene age (35–55 million years old) make up another fifth of the land, including central Sinai and central sections of the Eastern and Western deserts. The northern Western Desert is characterized by Miocene limestone (25–5 million years old). About one-eighth of Egypt’s surface—particularly the mountains of Sinai, the Red Sea region, and the southwestern Western Desert—is composed of ancient igneous and metamorphic rocks.

The fertile silt that supports today’s agriculture in the delta and Nile valley originates from the Ethiopian Highlands, carried by the Nile’s upper tributaries: the Blue Nile and the ʿAṭbarah rivers. Deposit depth ranges from over 30 feet (10 m) in the northern delta to about 22 feet (7 m) near Aswān. The White Nile, joining the Blue Nile at Khartoum in Sudan, contributes key minerals. Soil composition varies, tending to be sandier near the edges of cultivated land. Heavy clay can make soil difficult to work, while sodium carbonate concentrations sometimes produce infertile black-alkali soils. In the northern delta, salinization has created sterile soils known as barārī, or “barren” lands.

Climate

Egypt lies within the North African desert belt, which results in low annual rainfall, large seasonal and daily temperature variations, and abundant sunshine year-round. Desert regions occasionally experience cyclones that generate sand or dust storms called khamsins (Arabic: “fifties,” referring to roughly 50 days per year). These storms, most common from March to June, occur when tropical air from the south moves northward due to the extension of Sudan’s low-pressure system. Khamsins bring rapid temperature rises of 14–20 °F (8–11 °C), drops in humidity (often to 10%), thick dust, and gale-force winds.

Egypt’s climate is primarily biseasonal: winter lasts from November to March, and summer spans May to September, with brief transitional periods. Winters are mild, while summers are hot. January mean temperatures range from 48–65 °F (9–18 °C) in Alexandria to 48–74 °F (9–23 °C) in Aswān. June highs average 91 °F (33 °C) in Cairo and 106 °F (41 °C) in Aswān. Sunshine is abundant, with roughly 12 hours daily in summer and 8–10 hours in winter. Extreme weather, including heat waves and cold spells, can occur.

Humidity decreases from north to south and in desert areas. Along the Mediterranean coast, humidity is consistently high, especially in summer, which can make conditions oppressive. Rainfall is scarce and largely confined to winter, decreasing sharply southward. Alexandria receives around 7 inches (175 mm) annually, Cairo about 1 inch (25 mm), and Aswān only 0.1 inch (2.5 mm). The Red Sea coastal plain and the Western Desert are nearly rainless, while northern Sinai averages roughly 5 inches (125 mm) per year.

Plant and Animal Life

Despite limited rainfall, Egypt’s natural vegetation is diverse. Much of the Western Desert is barren, but areas with water support desert perennials and grasses, while the coastal strip blooms in spring. The Eastern Desert, though dry, sustains tamarisk, acacia, markh trees, thorny shrubs, succulents, and aromatic herbs. Vegetation is particularly lush in the wadis of the Red Sea Hills, Sinai, and ʿIlbah (Elba) Mountains in the southeast.

The Nile and irrigation networks support numerous aquatic plants, including the lotus of ancient times. Over 100 grass species grow near water, such as bamboo and esparto (ḥalfāʾ). Robust reeds like the Spanish and common reed are common in Lower Egypt, though papyrus now survives only in botanical gardens.

The date palm is widespread throughout the delta, Nile valley, and oases. The doum palm (Hyphaene thebaica) is associated with Upper Egypt and the oases, with scattered examples elsewhere. Few native trees exist; Phoenician juniper is the only native conifer. Widely cultivated trees include acacia, eucalyptus, sycamore, and imported species such as Casuarina (beefwood), jacaranda, royal poinciana, and lebbek (Albizia lebbek), which have become characteristic of the landscape.

Domestic animals include buffalo, camels, donkeys, sheep, and goats. Ancient fauna such as hippopotamuses, giraffes, and ostriches are no longer present; crocodiles survive only south of the Aswān High Dam. Wild animals include the aoudad (bearded sheep) in the southern Western Desert, Dorcas gazelle, fennec fox, Nubian ibex, Egyptian hare, and jerboas. Predators include the Egyptian jackal, hyrax (in Sinai), Caffre cat, and Egyptian mongoose. Reptiles are abundant, including monitor lizards and venomous snakes such as vipers, speckled snakes, and the Egyptian cobra (Naja haje). Scorpions and numerous rodents and insects, including locusts, are common.

Egypt hosts rich birdlife, with more than 200 migratory species and over 150 resident species. Common birds include the hooded crow and black kite, while birds of prey include lanner falcons, kestrels, lammergeiers, and golden eagles. Wading birds such as the great white egret, cattle egret, and hoopoe are present, though the sacred ibis is extinct locally. Desert birds number around 24 species.

The Nile supports about 190 fish species. The most common are bulṭī (Tilapia nilotica) and Nile perch. Delta lakes host būrī (gray mullet). Lake Qārūn in Al-Fayyūm has been stocked with būrī, and Lake Nasser with bulṭī, which grow to impressive sizes.

People of Egypt

Ethnic Groups

The population of Egypt is concentrated mainly along the Nile valley and delta, forming a relatively homogeneous group. Their physical characteristics reflect a mixture of indigenous African ancestry and Arab influence. Urban areas, particularly in the northern delta, have historically been more heterogeneous due to the presence of Persians, Romans, Greeks, Crusaders, Turks, and Circassians. Blond and red hair, blue eyes, and lighter complexions are therefore more common in towns, whereas rural delta populations—primarily peasant farmers, or fellahin—have been less affected by external intermarriage.

The middle Nile valley, extending roughly from Cairo to Aswān, is inhabited by the Ṣaʿīdī, or Upper Egyptians. While culturally more conservative, they are ethnically similar to Lower Egyptians. In the far south, Nubians differ both culturally and ethnically. Their kinship system is broader, encompassing clans and larger social segments, whereas other Egyptians generally recognize kinship only within the immediate lineage. Nubians have intermarried with Arabs and other groups, but their dominant physical traits remain those of sub-Saharan Africa.

The deserts of Egypt are home to nomadic, seminomadic, and formerly nomadic sedentary groups with distinct ethnic identities. In the Sinai and northern Eastern Desert, most inhabitants are recent Arab immigrants resembling Arabian Bedouin. Their social structure is tribal, with each group tracing its ancestry to a common forebear. Many of these groups have transitioned from nomadism to seminomadism or full settlement, particularly in northern Sinai.

The southern Eastern Desert is inhabited by the Beja, who closely resemble depictions of predynastic Egyptians. The Beja are divided into two tribes: the ʿAbābdah, occupying the Eastern Desert south of a line between Qinā and Al-Ghardaqah and along the Nile between Aswān and Qinā, and the Bishārīn, primarily in Sudan but with some presence in the ʿIlbah Mountains. Both tribes are nomadic pastoralists, raising camels, goats, and sheep.

In the Western Desert, outside the oases, inhabitants are of mixed Arab and Amazigh (Berber) descent, divided into the Saʿādī (distinct from Upper Egyptians) and the Mūrābiṭīn. The Saʿādī trace ancestry to the Arab tribes Banū Hilāl and Banū Sulaym, who migrated to North Africa in the 11th century, with the Awlād ʿAlī as the most prominent subgroup. The Mūrābiṭīn may descend from the region’s original Amazigh inhabitants. Initially nomadic, Western Desert Bedouin now live as seminomads or settled communities, with members dispersed widely rather than by clan.

The original populations of the Western Desert oases were Amazigh. Over time, they mixed with Nile Valley Egyptians, Arabs, Sudanese, Turks, and sub-Saharan Africans, especially in Al-Khārijah, the entrance point for the Darb al-Arbaʿīn (Forty Days Road) caravan route from Sudan.

Smaller foreign ethnic groups also exist in Egypt. During the 19th century, European communities—primarily Greek, Italian, British, and French—expanded rapidly, influencing finance, industry, and government. By the 1920s, foreign residents numbered over 200,000. Their presence has since diminished significantly after Egypt’s independence.

Languages of Egypt

Arabic is the official language of Egypt, with numerous regional vernaculars. Modern Standard Arabic (al-fuṣḥā), derived from Classical Arabic, is taught in schools and serves as the lingua franca among educated individuals throughout the Arab world. Its grammar and syntax have remained largely unchanged since the 7th century, though vocabulary and style have evolved under the influence of French and English.

Spoken vernaculars (al-ʿammiyyah) differ greatly from literary Arabic and vary regionally. Bedouin dialects in the Eastern and Western Deserts are distinct, and Upper Egypt has its own vernacular, markedly different from Cairene Arabic. The Cairo dialect is widely understood across Egypt and the Arab world, partly due to its role in the film industry and prolonged foreign influence, which introduced many loanwords. Many educated Egyptians are also fluent in English, French, or both.

Minor linguistic groups include the Beja in the southern Eastern Desert, speaking To Bedawi (a Cushitic Afro-Asiatic language) and sometimes Tigre, Siwa Oasis inhabitants with Berber-related languages, and Nubians, who speak Eastern Sudanic languages of the Nilo-Saharan family with Cushitic influences. Small communities of Greek, Italian, and Armenian speakers persist.

Historically, the Coptic language, derived from ancient Egyptian, was widely used until the 12th century, when Arabic became predominant. Coptic continues as a liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church.

Religion

Islam is Egypt’s official religion, with nearly all Muslims adhering to the Sunni branch. Al-Azhar University in Cairo is a leading global center of Islamic scholarship. Sufism is also widely practiced. The Muslim Brotherhood, founded in 1928, is a transnational organization promoting conservative Islamic values.

Christians are primarily Copts, the country’s largest Christian group. Copts share language, dress, and customs with Muslim Egyptians but maintain distinct religious rituals dating from before the Arab conquest in the 7th century. The Coptic Orthodox Church has remained largely unchanged since its split from the Eastern Church in the 5th century. Copts are traditionally associated with banking, commerce, civil service, and certain handicrafts, though some rural villages are entirely Coptic. They are concentrated in Asyūṭ, Al-Minyā, and Qinā, with about a quarter residing in Cairo.

Other Christian communities include Coptic Catholics, Greek Orthodox and Catholic, Armenian Orthodox and Catholic, Maronite, Syrian Catholic, Anglicans, and Protestants. Only a few Jews remain in Egypt.

Settlement Patterns

Egypt is physiographically divided into four main regions: the Nile valley and delta, the Eastern Desert, the Western Desert, and the Sinai Peninsula. Considering both physical and cultural characteristics, it can also be divided into subregions: the Nile delta, the Nile valley from Cairo to south of Aswān, the Eastern Desert and Red Sea coast, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Western Desert with its oases.

About half of the delta population are fellahin, small landowners or agricultural laborers. The remainder live in towns and cities, with Cairo being the largest. Urban residents have historically been more exposed to external influences than the more remote southern valley populations.

The Ṣaʿīdīs of the middle Nile valley are more conservative. In some areas, women still veil themselves in public, family honor is highly valued, and vendettas, though illegal, are culturally significant. The Aswān governorate, once remote and impoverished, has seen increased prosperity since the construction of the High Dam.

In the Eastern Desert, sedentary populations live mainly along the coast, with Raʾs Ghārib as the largest settlement. Nomads, comprising about one-eighth of the region, belong to tribes such as the Ḥuwayṭāt, Maʿāzah, ʿAbābdah, and Bishārīn. They rely on herding or trade with mining, petroleum camps, or coastal fishing communities.

The Western Desert, outside the oases, is mainly inhabited by the Awlād ʿAlī tribe. Less than half remain seminomadic; others are settled, engaging in agriculture, fishing, trading, and handicrafts. Marsā Maṭrūḥ, a Mediterranean resort, is the only urban center. Oases, such as Al-Khārijah, Al-Dākhilah, Al-Farāfirah, Al-Baḥriyyah, and Siwa, are ethnically and culturally distinct and increasingly developed through reclamation projects.

The Sinai Peninsula is predominantly Arab, with settled populations around Al-ʿArīsh and the northern coast, while central and mountainous areas remain nomadic or seminomadic. Al-Qanṭarah, near the Suez Canal, also hosts a sedentary population.

Rural Settlement

Rural settlements across the Nile delta and valley are generally homogeneous. Villages are compact, surrounded by cultivated fields, and typically house 500–10,000 people. Common landscape features include date palms, sycamores, eucalyptus, and Casuarina trees. Many villages are built along canals or on mounds, remnants of basin irrigation and annual flooding.

Delta houses are usually one or two stories, made of mud bricks plastered with mud and straw. Southern Nile valley houses often use more stone. Roofs are flat, made of date-palm leaves and wood rafters, and store maize, cotton stalks, and dung cakes for fuel. Grain is stored in small mud silos on rooftops, which also serve as sleeping areas during hot nights.

Poorer homes consist of a narrow passage, a bedroom, and a courtyard, sometimes housing livestock. Prosperous homes use burnt bricks and concrete, with modern amenities. Villages typically feature a mosque or church, primary school, pigeon cote, government service buildings, and shops. Roads are mainly unpaved dirt tracks, with at least one motorable road per village.

Western Desert oases have dispersed settlements, with modern houses two stories high and more widely spaced than traditional six-story mud constructions.

Urban Settlement

Many Egyptian “urban” areas are overgrown villages, with residents engaged in agriculture and related work. Towns that gained urban status in the 20th century often retain a rural character, although they now include officials, traders, industrial workers, and professionals. Urban expansion has encroached on farmland, with buildings often constructed without formal planning.

Typical buildings in towns and small cities are two-story houses or four- to six-story apartment blocks, with better structures lime-washed and featuring balconies. Unpainted red brick and concrete are common for other buildings.

Some cities, like Cairo, Alexandria, and Aswān, have distinct characteristics. Cairo, a sprawling metropolis, reflects more than a millennium of architectural history. Greater Cairo, Alexandria, and key towns along the Suez Canal—Port Said, Ismailia, and Suez—are modern urban centers comparable to cities worldwide.

HurghadaToGo – Red Sea Services

HurghadaToGo offers a full range of services along the Red Sea, including airport transfers, private and group excursions, snorkeling and diving trips, boat tours, and island visits. With professional guides, comfortable transport, and personalized packages, we ensure every guest enjoys a safe, seamless, and unforgettable Red Sea experience.

Easy & Secure Booking

Reserve your unforgettable Hurghada to Cairo and Alexandria private tour 2026 now through:

🌐 Official Website: hurghadatogo.com

📧 Email: [email protected]

📱 WhatsApp: +201009255585

We also recommend you :

Hurghada to Cairo and Alexandria private tour 2026