Hurghada Famous Places: What Most Guides Don’t Tell You Welcome to the ultimate insider’s guide to Hurghada. If…

Cairo Day Trip by Bus from Soma Bay 2026 is the perfect choice for travelers who want to…

Unveiling the Hidden Heart of the Great Pyramid: Groundbreaking Muon-Imaging Discoveries Rewrite What We Thought We Knew For…

Jahuti Egypt (Djehuty) in Ancient Egypt The term “Jahuti” (also spelled Djehuty, Jehuti, or Tahuti) primarily refers to…

The New Egyptian Museum: A Monumental Leap into History at the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza For centuries,…

The Nubian Egg: An Ancient Artifact and Its Mysteries The author claims these pyramids refers to the Giza…

The Hidden City Beneath the Pyramids The Mystery of a “Hidden City” Beneath the Pyramids of Giza The…

Kings of nile with crowns of gold The phrase “kings of Nile with crowns of gold” likely refers…

Anubis: The Jackal-Headed Guardian of the Egyptian Afterlife Imagine standing at the edge of the Nile, the sun…

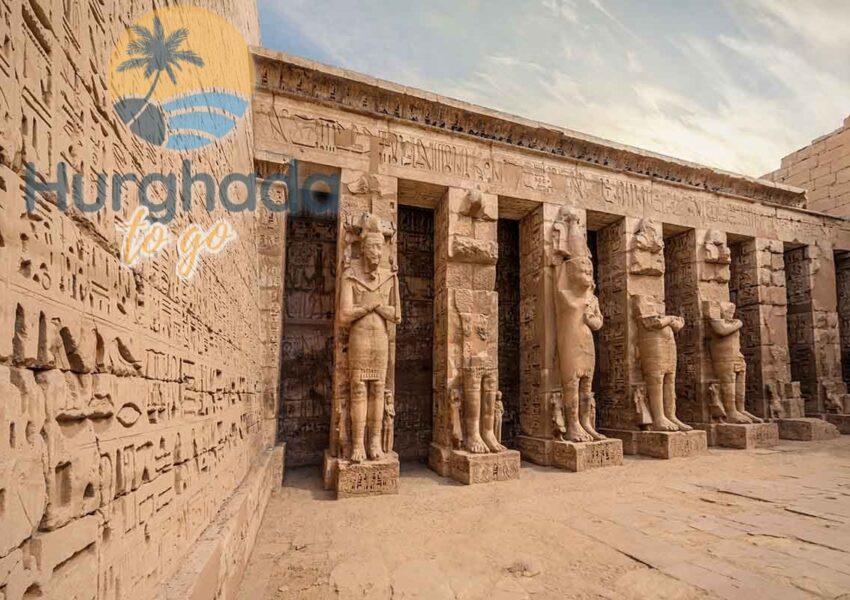

Medinet Habu: Egypt’s Hidden Gem of the New Kingdom Nestled on the West Bank of the Nile in…